Nineteenth Century House

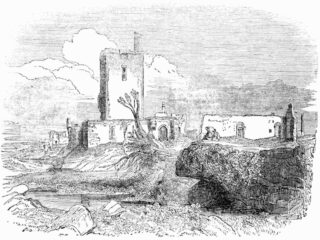

The most recent of these structures appears to have been a house that was built directly onto the south face of the tower house during the mid-nineteenth century and likely belonged to Edmund O’Flaherty – a local landlord, innkeeper, farmer and postmaster. Edmund was a descendant of the once powerful O’Flaherty family who had ruled the medieval lordship of Iarchonnacht for nearly four hundred and fifty years as Gaelic warrior lords. Aughnanure Castle was the jewel in the crown of the O’Flaherty network of tower houses, built along the coastal fringes of their remote western territory and along the shores of Lough Corrib. Following their final loss of Aughnanure in the eighteenth century, it had gradually fallen into disrepair and stood empty and broken, a mere shadow of its former self.

Over the succeeding centuries, Aughnanure Castle fell into the hands of several owners including Captain James O’Hara of Lenaboy Castle in Galway, while his tenant, Edmund O’Flaherty, originally from nearby Gortrevagh, Oughterard, utilised the ruinous castle and lands as a dairy farm during the late nineteenth century. A two-story, three-bay stone building was added to the castle during this time. The Tuam Herald dated February 26th, 1870 reported Edmund O’Flaherty being “of Aughnanure Castle” when announcing the marriage of his son George Edward to Emilia Sayers, suggesting that he may have been living in the house attached to the castle at the time. By 1873, Edmund held a total of 2,091 acres of land around Oughterard and Ballyconneely.

Some possible evidence of Edmund’s activity from this period was also uncovered during the course of the summer when one eagle-eyed guide came across clay pipe and pottery pieces while simply walking the grounds of the castle. The extremely dry conditions caused the grass to thin and the soil to dry and crack to such an extent that objects became clearly visible on the ground’s surface. Three clay pipe pieces and four ceramic fragments were discovered (figures 2 & 3). One of the clay pipe fragments appears to date to a much earlier period, possibly the later half of the seventeenth century. The bowl is thin, slender and undecorated and is probably contemporary with the Earl of Clanricarde’s temporary occupation of the castle after 1640. Aughnanure Castle had temporarily passed into the possession of the 5th Earl of Clanricarde, Ulick Burke, following the extension of his lordship as a result of the Acts of Settlement of the 1650’s.

However, the two remaining clay pipe fragments appear to have come from the same pipe and are marked with “O’GORMAN GALWAY” on the bowl. These two fragments can be dated to the late nineteenth century and were produced by a maker operating at Mill Street in Galway from at least the second half of nineteenth century. This pipe is more than likely associated with Edmund’s occupation of the house at Aughnanure Castle during this period. The smoking of clay pipes became popular in Ireland before the introduction of cigarette smoking in the twentieth century and they played an important role in everyday life and custom, especially in rural communities. The growth in popularity of clay pipes was generated from their association with cultural traditions and as a result, they were mass-produced throughout the country. It is highly likely that Edmund O’Flaherty smoked one of these clay pipes. The ceramic fragments are likely from plates and one displays the popular blue and white willow pattern. Ceramic pieces like plates, mugs and bowls were in everyday use during the nineteenth century but were highly valued for their decorative function. We can only presume that ceramic pieces like these took pride of place on Edmund’s family’s kitchen dresser.

A photo of Aughnanure Castle from the Lawrence Collection (figure 4), taken just before the turn of the twentieth century show that Edmund’s house had been abandoned and was in a semi-ruinous condition. Later photos from the 1940s (figures 5 & 6) reveal the house had dilapidated even further. The photos did indeed confirm that a house, presumably Edmund’s, stood in the exact location of some of the ground marks revealed last summer. Scars of the roofline left behind on the south wall of the tower house reveal the only remains of that house today (figure 7). However, this was not the full story. There were still other ground marks that remained unidentified. What did these marks correspond to?

The Sixteenth Century Kitchen

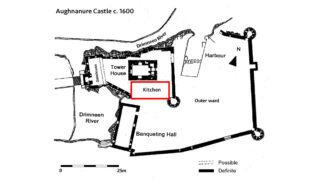

It is possible that Edmund’s house was incorporated into a much earlier structure, potentially associated with the building of the banqueting hall in the second half of the sixteenth century. This was a later phase of building at Aughnanure following the initial construction of the tower house and bawn at the end of the fifteenth century.

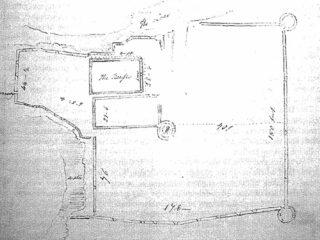

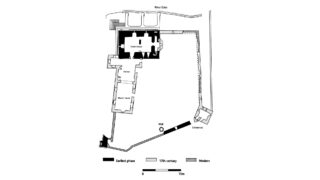

During his work as a draughtsman with the Topographical Department of the Ordnance Survey of Ireland, William Wakeman, who had studied under Victorian archaeologist and antiquarian, George Petrie, produced pencil sketches and plans of the castle when he visited in the summer of 1839 (figures 8 & 9). He included a rectangular building almost parallel to the south of the tower house in his plans, corresponding exactly to the other previously unidentified ground marks. But what was this building’s function?

The answer came from two highly descriptive accounts of the castle, both dating to the nineteenth century. In 1840, the writer for the Irish Penny Journal recorded additional buildings surrounding the O’Flaherty tower house:

His house, a strong and lofty tower, stands in an ample courtyard, surrounded by outworks perforated with shot-holes, and only accessible through its drawbridge gateway-tower. Cellars, bake-houses and houses for the accommodation of his numerous followers, are also to be seen.

In a similar account in an article written in 1859 for The Dublin Builder, the writer again describes several buildings in the immediate vicinity of the tower house including:

the great kitchen, with its enormous fireplace, its huge cellars and culinary offices, with accommodation for numerous retainers surround the dwelling.

It is entirely possible that the structure to the south of the tower house that Wakeman included in his plans was this “great kitchen” in almost the exact spot that would later occupy Edmund’s house. The tower house itself does not show any evidence of large-scale cooking being carried out therefore it is reasonable to suggest that a separate kitchen building was constructed to perform culinary functions. This becomes even more credible with the addition of a large and spacious banqueting hall during the late sixteenth century, which would have undoubtedly necessitated the need for a large kitchen in order to prepare and cook food for the typical lavish feasting rituals of a Gaelic lord. The kitchen building is therefore likely contemporary with the second phase of construction at Aughnanure along with the banqueting hall and outer bawn wall (figure 10). The placement of additional buildings between tower houses and halls is not unusual, and a similar arrangement can be seen at Kilcolman Castle in north Co. Cork where a “parlour” was added between the tower house and hall (figure 11). Similarly, at Donegal Castle, a kitchen is placed centrally between the earlier tower house and later manor house (figure 12).

The Kitchen Disappears

By 1867, Sir William Wilde had published Lough Corrib – It’s Shores and Islands and during that time it appears that a more modern structure occupied the site of the great kitchen i.e. Edmund’s house. Wilde visited the castle and recorded the site of the great kitchen:

Nearly parallel with the great tower and in connection with the western angle of the round house, there existed some years ago the remains of another building, 23 and a half feet wide, but this has been for some time removed; and its site is at present occupied by a modern structure.

Did Edmund actually remove the “great kitchen” or did he incorporate it into his house? Perhaps he had such a strong desire to live in the shadow of his ancestors and to perpetuate the family name there that he did indeed retain some vestiges of the great kitchen in his home. Edmund was a descendant of the Moycullen branch of the O’Flahertys and appears to have felt a strong connection to his ancestral home. He had become a successful landlord himself, yet felt a need to lease Aughnanure Castle from another landlord and build a residence there, even though the tower house had long fallen into ruin. An amateur antiquarian, during his lifetime he discovered some archaeological artefacts around Aughnanure Castle and its immediate vicinity and presented them over to the National Museum of Ireland. These included a Neolithic log boat, a late medieval iron key, a lead musket ball, cutting blades, hooks, knife blades, a crucible and several glass fragments. These objects are currently in storage in the National Museum. In 1843 Edmund even went to the trouble of planting several young yew trees at the castle in memory of the placename Aughnanure, from the Irish “Achadh na Iúr” or “Field of the Yews”. One of these still survives and can be see at the entrance of the castle today.

The Future?

While it is tempting to speculate that Edmund did indeed incorporate his home into the great kitchen of his fore-bearers, especially given his background and apparent interest in his ancestry, it is impossible to say without any evidence or further investigation. No upstanding traces of these structures remain on the grounds of Aughnanure today but we are fortunate that last years exceptional conditions offered an opportunity to glimpse into the castle’s long and diverse history and reveal a secret or two of its past.

Furthermore, this new information provides fresh and unique insights into the development of the late medieval landscape and society of the O’Flahertys at Aughnanure Castle and offers an extraordinary glimpse into the domestic architecture of a Gaelic lord. It reinforces the remarkable level of use of the landscape around the tower house during its second phase of building and has the potential to transform our understanding and interpretation of the site. The kitchen, visible only fleetingly as ground marks during the dry summer, clearly forms a deliberate structure of significance built in the shadow of the O’Flaherty’s most prominent castle. This discovery raises many questions and will hopefully provide a basis for a solid and refreshed research framework to be implemented in the future.

Bibliography

- Wilde, William R. (1867) Lough Corrib – It’s Shores and Islands: With Notices of Lough Mask. McGlashan and Gill, Dublin.

- Petrie, George. (1840) The Castle of Aughnanure. The Irish Penny Journal. Vol. 1 No. 1.

- Anon. (1859) The Castle of Aughnanure, Connemara. The Dublin Builder. Vol. 1 No. 7.

About the Author

Jenny Young holds a BA in Archaeology & Geography and a MA in Landscape Archaeology from NUI Galway. She works at Aughnanure Castle and has developed a passionate and broad interest in medieval Gaelic settlement and society. She is currently undergoing research into the medieval Gaelic lordship of Iarchonnacht for a future publication.