The Irish School of Illumination

One of the most substantial accomplishments in the Irish tradition of education was the introduction of the written word. It is generally believed that a form of archaic Irish found in Ogham inscriptions, mostly on stone and dated to the fourth century, constitutes not only the earliest written examples of the Irish language, but some of the oldest vernacular literature in western Europe. This writing predates the earliest extant examples of Old Irish proper. These are found in the margins of Latin manuscripts, most of them preserved in monasteries in continental Europe, having been brought there by early Irish missionaries. This early form of Irish writing belongs to the period after the introduction of Christianity to Ireland; in fact, many of the early texts were produced specifically to aid in the process of conversion. But what developed from around the seventh century was an interaction between Latin, the Irish language and the ancient oral traditions and practices of poetry, satire and mythology that encouraged literature and the arts to blossom in the burgeoning monastic complexes. This was the beginning of a vibrant literate culture that led to a remarkable flourishing of literature in Ireland in manuscript form.

In this period, Ireland retained a cohesive society characterised by rural monastic settlements, from which Irish missionaries spread Christianity, bringing strongholds of Irish Christian influence to Britain and continental Europe. In doing so, they transmitted a new style of art throughout north-western Europe, called insular art. This style, in which numerous books and manuscripts were produced, was essentially a blending of Celtic, Classical and, later, Germanic artistic traditions. Its dense and intricate decoration embodied a pivotal moment in the development of early Christian art. The most characteristic features of this art form are rooted in the late Iron Age La Tène tradition of Celtic art and include interlace decoration, formal patterns of spirals, plant ornament, naturalistic animals, bird and human figures. Another distinguishing trait of insular art is the fusion of figurative and ornamental decoration, with some elements so stylised that they appear almost abstract. The insular style evolved from the fifth century, but reached its pinnacle during the ninth century, continuing in Ireland into the twelfth century.

Though the early Irish literary tradition is represented by a large corpus of manuscripts and books, the most celebrated are the Illuminated manuscripts from the period between the seventh and early twelfth centuries. These embody the zenith of Ireland’s insular artistic history and demonstrate the skill and artistry of the scribes who created them. The revered illuminators are even believed to have received divine aid in the creation of these manuscripts. Veneration for their work was often expressed in supernatural terms, describing it as the work of “angels” rather than mere mortals. This is hardly surprising, given the exquisite precision and extreme delicacy with which these manuscripts were executed. The painstaking attention to detail that defines this art form is almost Herculean in its mastery.

The mechanisms by which these artistic skills were transmitted, however, were not divine. The growth of the Church meant that there was a constant need to copy bibles and other religious books that were brought to Ireland by Christian missionaries. As a result, ordinary monks in monastic complexes throughout Ireland had the monopoly of education, quickly developing important schools and luring students from Britain and continental Europe. The reproduction of books was needed for general religious study but also for the services in the choir and readings in the refectory. However, the making of new manuscripts required significant resources, including a repository of books from which to make copies and access to writing materials like vellum, parchment and pigments. Consequently, by the ninth century it is likely that the production of books was limited to a number of major monastic centres including Clonmacnoise, Kildare and Armagh.

The scriptorium was one of the most active buildings in the monastic complex, where the arts of calligraphy and decoration, as well as scripture, Latin, philosophy, grammar and astronomy, were practised and taught. Here the monks devoted considerable attention to writing and decoration, developing their own unique form of script. The monastery’s calligraphers and scribes had the laborious task of copying the chosen religious texts word for word, while the illuminators would undertake the illustrations. These scriptoria were responsible for the stunning illustrations and calligraphic art contained within the most renowned illuminated manuscripts. Information was passed on from one generation to the next and this process of education was fundamental to the continuance of this artistic tradition.

The culmination of this process of learning was manifest in the artistry of the illuminated manuscripts, and is associated with some of Ireland’s most iconic monastic sites, including Clonmacnoise, Kells, Roscrea, Durrow and Monasterboice. Larger manuscripts like the Book of Kells were, in their most practical application, used as altar books intended for liturgical reading but, when required, were often displayed as extravagant ornamental pieces in ceremonial contexts. The smaller manuscripts or “pocket-books”, on the other hand, including the Book of Dimma and the Book of Mulling, were intended for study and easy transport. Regardless of their function, the manuscripts always had a spiritual focus, containing reproductions of the sacred texts of the bible.

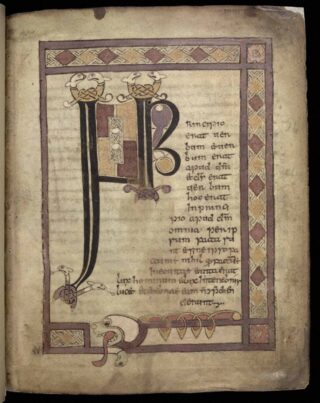

The Book of Durrow, c. AD 650–700

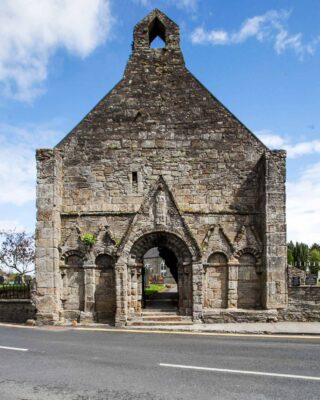

Associated Site: Durrow Abbey, Co. Offaly

The tentative beginnings of elaboration of the large initial capital letters of paragraphs is witnessed in the Cathach of St Columba, c. 600, but the techniques and level of embellishment was increased and developed in the following century in the Book of Durrow. The oldest extant complete illuminated insular Gospel book, the Book of Durrow represents one of the most important artistic manuscripts of seventh-century Europe. It was probably used for missionary or teaching purposes, carried in a small leather pouch. The book has a long association with Durrow Abbey, Co. Offaly, although the place of its creation still remains uncertain. The original monastic settlement at Durrow was founded in the mid-sixth century by St Columba. Durrow and Armagh were referred to as “the Universities of the West”, a testament to their reputation as seats of learning.

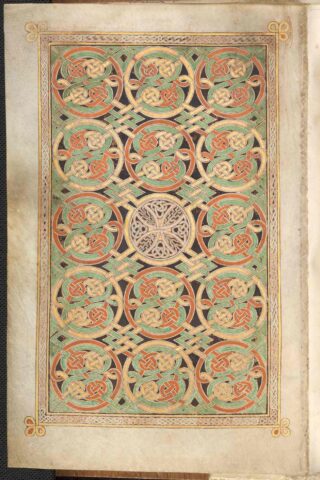

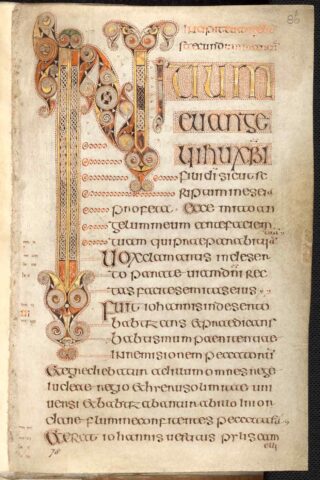

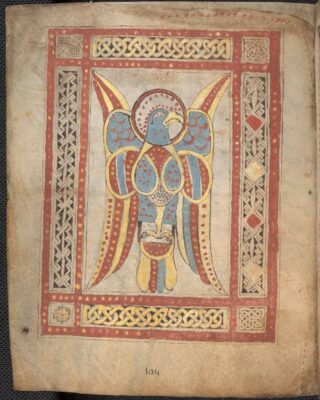

The fully developed insular style is witnessed in the Book of Durrow, where the ornament is mainly concentrated at the beginning of each Gospel. However, the major stylistic features are illustrated in the “carpet pages”, folios that are patterned all over in the manner of an oriental carpet. The traditional flowering style of Celtic art produced the book’s six carpet pages, which are vividly dominated by red, yellow and green zoomorphic interlaced patterns of a kind not before seen in the insular world. These beautiful, fully decorated pages typically preface each of the four Gospels and usually contain an intricate set of geometric or Celtic interlace designs, which can be curvilinear, flowing and endlessly repetitive, although no detail or motif is ever exactly repeated. The double-armed crosses, trumpet spirals and interlacing circles are strongly reminiscent of metalwork and jewellery, while the five Evangelist portraits are executed with remarkable delicacy. The manuscript remained at the abbey of Durrow until the mid-seventeenth century, when it was acquired by the library of Trinity College Dublin.

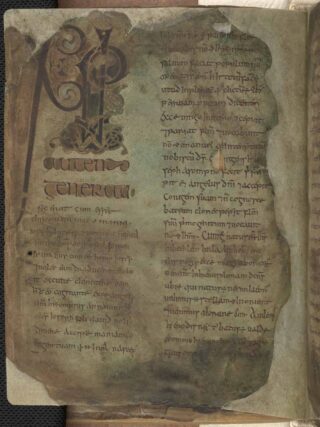

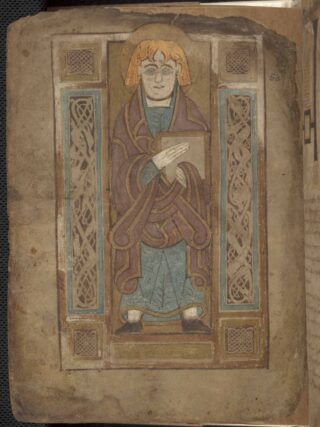

The Book of Dimma, c. AD 750

Associated Site: St Cronan’s Church, Roscrea, Co. Tipperary

Scribal traditions are also associated with the early ecclesiastical settlement of St Cronan in Roscrea, Co. Tipperary. At a crossroads on the Slighe Dhála, one of the principal routeways of ancient Ireland, the church at Roscrea was established some time in the late sixth or early seventh century. This was the setting for the creation of the pocket Gospel Book of Dimma, written sometime in the late eighth century, when Roscrea had become a place of some importance. The small volume not only contains the four Gospels, but also a later-inserted supplemental text of a ritual for the visitation of the sick. Owing to its modest dimensions, the programme of decoration is somewhat reduced, mainly comprising some Evangelist portraits and illuminated initials. However, its style and use of ornate colours are reminiscent of the Gospel books produced at Lindisfarne, off the coast of Northumberland.

By the twelfth century the manuscript was encased in a richly worked bronze and silver book shrine or cumdach and it is likely that both remained at Roscrea for several centuries. The Book of Dimma fell into the hands of both Henry Monk Mason and William Betham in the early nineteenth century, before being purchased for the Trinity College Library collection in 1836.

The Book of Mulling, c. AD 750

Associated Site: St Mullin’s Monastic Site, Co. Carlow

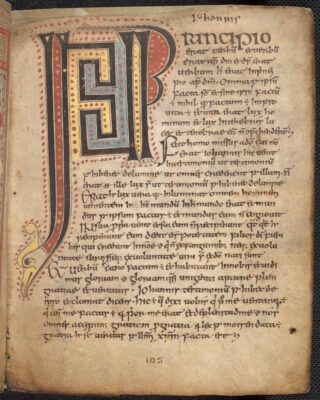

Another important achievement in insular art is the Book of Mulling, written at the monastery of Teach-Moling, Co. Carlow (now St Mullin’s) at the end of the eighth century. Similar to the Book of Dimma, this was produced as a pocket Gospel, written in Irish minuscule script and therefore employing an informal style of text. The text comprises the four Gospels, each elaborated with decorated initials, their letters formed with zoomorphic interlace and ornamented with knotwork, but also incorporates a liturgical service that includes the Apostles’ Creed. The ornamentation, embellishments and portraits employ a good range of colour. The canon tables and a text for a service of the visitation of the sick appear to be later additions from the ninth century, and also what appears to be a diagram of the monastery at St Mulling’s, but this is still under much scrutiny and study.

The Book of Mulling is associated with a fourteenth-century silver and copper jewelled book shrine that has an inscription relating to the king of Leinster, Art MacMurrough. The book and its shrine remained with the MacMurrough-Kavanagh family until the late eighteenth century, when the family presented both to the library of Trinity College Dublin. While the book passed into the library’s collection, the shrine was placed on loan at the National Museum of Ireland in 2001.

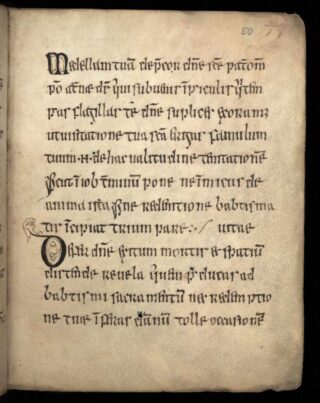

The Stowe Missal, c. AD 790

Associated Sites: Lorrha Priory of St Ruadhan, Co. Tipperary and Lackeen Castle, Co. Tipperary

Another landmark in the development of the insular manuscript was the Stowe Missal. The first inscription on the shrine of the late-eighth century sacramentary attributes its production to the monastery of St Ruadhan in Lorrha, Co. Tipperary. However, this claim still remains unverified. It is possible, however, that the book was first produced elsewhere, perhaps at Terryglass, Co. Tipperary or at St Maélruáin’s monastery in Tallaght, Co. Dublin, before travelling south to Lorrha in the eleventh century, where it was annotated, enshrined and venerated as a relic. Its association with Lorrha remains significant nonetheless, as the illuminated manuscript is still widely known as the Lorrha Missal.

The pocket service book contains the texts necessary for the performance of liturgical services and mass, including chants, prayers and readings, written in both Latin and Irish in a cursive minuscule script. It is possible that the book was highly practical and regularly used by priests who travelled long distances to celebrate mass in remote communities. The first part of the book contains excerpts from the Gospel of St John, written in Latin, while the second part contains a theological tract on the mass, written in old Irish. Three texts for healing ailments were added to the book in the eleventh century or later, also written in old Irish. Characteristic of the pocket Gospel group of manuscripts, high-grade decoration in a small format is seen throughout, while the opening page of the Gospel has a large ornamental initial with decorative borders of colourful geometrical patterns.

An elaborate book shrine was created for the Stowe Missal while it was still at Lorrha in AD 1033. It remained there into the fifteenth century, before getting lost for some time. Following the book’s dramatic rediscovery in the late eighteenth century, within the walls of Lackeen Castle in Co. Tipperary, it became part of a manuscript collection of the duke of Buckingham at Stowe House in England. The book was eventually purchased by the British government in 1883 and has been preserved in Dublin’s Royal Irish Academy ever since.

The Book of Kells, c. AD 800

Associated Site: The Monastery of Kells, Co. Meath

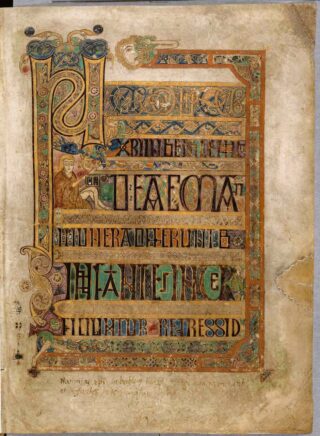

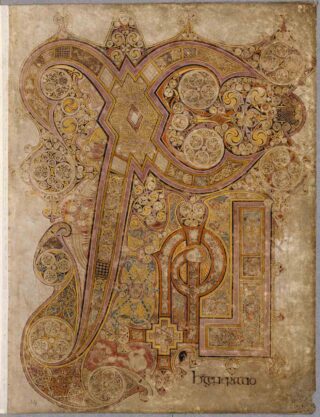

As exquisite as the books of the seventh and eighth century may be, a significant development in exceptional manuscript illumination reached its height in the early ninth century with the Book of Kells, perhaps the greatest work of Irish visual art. It was with the production of this book that insular illumination attained its fullest and most distinctive development. Extraordinary and unrivalled, its significance has never been underestimated; it was described in the Annals of Ulster in 1007 as “the chief treasure of the western world”.

At the dawn of the ninth century a monastery was established at Kells, Co. Meath by the monks of Iona, off Scotland’s western coast, a monastery founded by St Colmcille in AD 563. The Book of Kells has retained its association with this monastic complex, but debate still surrounds its provenance. It remains unknown whether the manuscript was begun in Iona and continued at Kells, written entirely in Iona or written entirely in Kells. Nonetheless, this supreme masterpiece is undoubtedly the most celebrated of all Irish illuminated manuscripts. It contains the four Gospels of the New Testament together with various prefatory texts and tables, written in Latin.

The continuing fashion of full-page illustration, much of which decorates the Gospel passages and the portraits of Christ and the Evangelists, was brought to its apex in the Book of Kells. The importance of these illustrated pages is one of the significant and dazzling features of the book. Rich illustration is found throughout in a diverse repertoire of decorative embellishments of both abstract and representational art, including trumpet ornaments, interlace design, geometric patterns, Celtic crosses, mysterious fantastical beasts, birds and animals. The profusion of ornament, composed of sumptuous swirling motifs typical of insular art, is combined with traditional Christian iconography. The ornament is both complex and accomplished and its extent and artistry is incomparable, while the impeccable text has a formal, print-like quality. Embellishment of extraordinary variety and delicacy is witnessed on the renowned Chi Rho page, which depicts the monogram of the Greek form of Christ’s name, has led experts to liken the skills of the artist to those of a goldsmith. Interlacing, knotwork and spirals encompass the most universally characteristic ornaments and are innovatively applied and developed with elegance, used in regularly repeating panel patterns. These distinctive patterns exemplify insular art and are found in both the Book of Kells and Book of Durrow. These are designed to reinforce the meaning of the religious drawings they adorn, representing eternity, faith and the endlessness of life, death and spiritual rebirth.

The book remained at Kells throughout the Middle Ages but, following the 1641 Rebellion, the church lay in ruins. In the interest of the book’s safety and preservation, the governor of Kells sent it to Dublin, where it eventually reached the library at Trinity College. It still remains there on permanent display.

The Cotton Psalter, c. AD 900

Associated Site: Monasterboice, Co. Louth

The tradition and skills of insular decoration continued into the tenth century, though much less ambitious or accomplished. This is witnessed in the Cotton Psalter, demonstrating the continuing production of small illuminated psalm books. Possibly a product of Monasterboice, Co. Louth, founded in the sixth century by St Buite, the monastery remained an important centre of literature and learning between the eighth and twelfth centuries, with a famous scriptorium and library. Though it maintained strong intellectual links with other ecclesiastical institutions such as Armagh, Clonmacnoise and Slane, it was gradually superseded by the nearby Cistercian foundation of Mellifont in the twelfth century.

Despite being badly damaged by fire in 1731, some pages of the Cotton Psalter have decorated, interlaced borders with animal terminations and initials that survive at the beginning of each psalm, while the text is clear and legible. The ornament of the book in general, however, is much more limited than its lavish predecessors. Two highly stylised miniatures depict David and Goliath surrounded by panelled borders of interlaced patterns, while in the centre David plays a lyre with an asymmetrical frame, seated on a lion with curved paws. The whole scene is reminiscent of a similar scene depicted on the south cross at Monasterboice.

The Cotton Psalter is named after English antiquarian Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, who added it to his collection of manuscripts in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. The library he established was inherited by his son and then by his grandson, who negotiated the transfer of the entire collection to the English nation in the early eighteenth century, which eventually became part of the newly established British Museum.

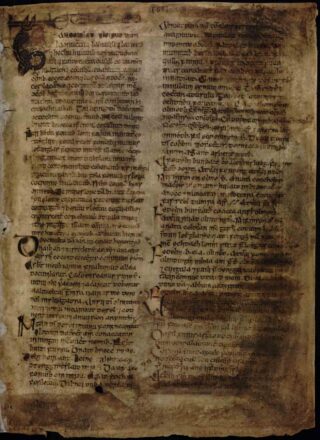

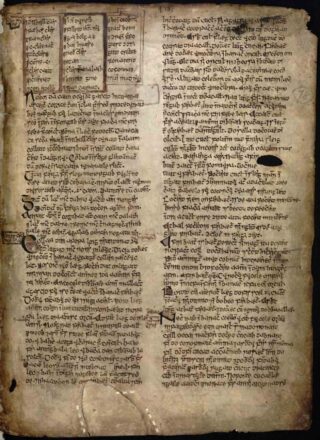

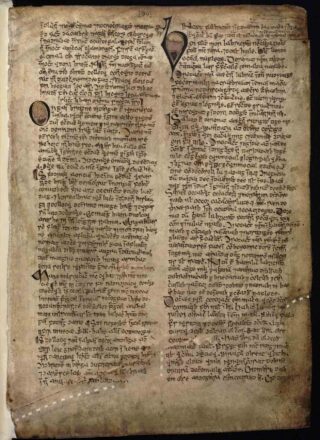

Lebor na hUidhre, c. AD 1050–1100

Associated Site: Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly

The range of manuscripts of the late eleventh and twelfth centuries is wider than the earlier periods, reflecting the broadening interests of Irish ecclesiastical scholars. While Gospel books, psalm books and missals still reflect the majority of volumes produced, annals, genealogies, sagas and poetry were becoming increasingly popular. However, the heyday of illumination had passed and illumination was only practised in the richest and most powerful monasteries.

Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly remained powerful into the early twelfth century, when Lebor na hUidhre or the Book of the Dun Cow, the oldest extant manuscript written in the Irish language, was produced there. According to legend, the book was made from the hide of a dun cow by St Ciarán of Clonmacnoise. It contains a large collection of diverse texts, including some religious passages, poetry and the oldest versions of a number of celebrated Irish legends, including the Táin Bó Cuailgne, or Cattle Raid of Cooley, and the Voyage of Bran. The decoration of the book is very conservative, suggesting the scriptorium at Clonmacnoise was firmly rooted in tradition. The ornament of the book is restricted to delicate decorative initials, the majority of which consist of knotted wire and ribbon animals. The text is mostly in two columns, written in a regular Irish minuscule. Lebor na hUidhre represents a transition from the ecclesiastical Latin texts of the earlier illuminated books, to the collections of Irish texts found in the decorated books of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Following the break-up of the monastery at Clonmacnoise, the manuscript came into the possession of several hands and was lost on numerous occasions over the centuries. It remained in Donegal until the mid-seventeenth century, eventually turning up in the Hodges & Smith Collection of manuscripts, which was purchased by the Royal Irish Academy in 1844.

The Irish School of Illumination reached an extraordinary degree of excellence between the seventh and early twelfth centuries. This was the beginning of a golden age of artistic achievement in Ireland. In the whole history of illumination it can be argued that the execution of the Irish School was never surpassed. The monasteries that produced the manuscripts demonstrated an exceptional level of scholarship and skill rarely exceeded by even the most eminent schools in all of Europe. The manufacture of these technically complex manuscripts was a huge undertaking, as each one was entirely handmade. Every manuscript was therefore a unique piece of art in which the work of the scribes and illuminators was executed with superb delicacy and an indescribable perfection of finish. The excellence of their workmanship reveals their deep understanding of art, masterly dexterity, attention to detail and perfect rendering. These technical capabilities allowed the scribes to meet the most trying demands of complex and difficult designs with remarkable skill.

The monastic scriptoria retained their monopoly of book production for centuries. However, in the period following the twelfth century, manuscripts were no longer produced solely for monastic use. A demand for books from lay patrons by secular professional scribes from the learned families grew, while the invention of the printing press and rising levels of literacy brought about a general decline in the practice of creating handmade illuminated manuscripts. But the artistic and literary significance of this transmitted culture has stood the test of time, helping to define the country in a cultural-historical sense while continuing to teach us about the value of educational and cultural exchange. Indeed, the tradition of manuscript illumination plays a crucial role in telling the story of early medieval Ireland and how the process of education was central to the transmission of knowledge across generations to produce these works of art. That golden age of Irish art ensured the manuscript’s unique place in the history of western European civilisation, which has left a lasting legacy in both Ireland and the rest of the world and continues to engage and inspire our imaginations.