The Mesolithic

8000–4000 BC

Evidence of Ireland’s prehistoric past can be seen all around us. Countless monuments from burial mounds to homesteads lie buried just beneath the surface. Sometimes they are still very much visible as imposing monuments that dominate their locality. Sites such as the Boyne Valley complex in Co. Meath or Carrowkeel Cemetery in Co. Sligo demonstrate the potential for prehistoric monuments to be impressive features and to illuminate the numerous skills possessed by the people who built them.

These built monuments do not, however, represent the first people to make these shores their home. Ireland was colonised by human beings approximately 10,000 years ago during a period of the Stone Age referred to as the Mesolithic. These people did not build large monuments or live in large settled communities and therefore it is difficult to draw conclusions about their lives and nature. What is clear, however, is that they lived in small groups and had expertise in acquiring what they needed from the landscape to survive.

Often referred to as hunter-gatherers, these people used their knowledge of seasons and nature to exploit locally and temporarily abundant resources such as salmon or hazelnuts. They often settled temporarily close to the resources they harvested, at encampments such as the one at Lough Boora, Co. Offaly, dated to around 6500 BC. Evidence of the material culture of these people unfortunately has not generally survived, with some notable exceptions such as the 7,000-year-old fish trap discovered at Clowanstown, Co. Meath. It can be seen from examples such as this that the Mesolithic inhabitants of Ireland were excellent craftspeople. With so little evidence, the mechanisms of education and transmission of these skills can only be speculated, but several assumptions can be made. We can infer that the timing of natural phenomena relating to food was well known and exploited; that this information was passed on from generation to generation; and that the process of education was crucial to the survival of these communities.

The Neolithic

4000–2400 BC

Associated Sites: Céide Fields, Co. Mayo, Brú na Boinne, Co. Meath, Lough Crew, Co. Meath, Carrowmore, Co. Sligo and Carrowkeel, Co. Sligo

Ireland’s First Farmers: The Céide Fields, c. 3500 BC

The arrival of agriculture had a profound effect on the people and landscape of Ireland. People settled and started to build more permanent dwellings close to the land, which they cleared of trees and brought under the plough. Domestic animals such as cows, sheep and pigs were introduced at this time, as well as many cereal crops, and both came to replace the wild foods of the Mesolithic.

The Céide Fields on the north coast of Co. Mayo, dated to approximately 3500 BC, are perhaps the best example of a Neolithic farming landscape where an entire system of drystone walls can be seen dividing up the land into fields for agriculture for the first time. Subsequent changes in climate have made Ireland a wetter place, and over thousands of years the bogs grew to cover the entire area around Céide, sealing and preserving the Neolithic landscape. The Céide Fields are not alone, however, in providing us with such evidence. The adoption of agriculture can be seen in monuments all over the country as similar buried field systems, sometimes on the coast and sometimes in upland environments.

These people were farmers above all else, living in what would seem to have been a largely peaceful society. Their land would have been their most valued asset and the transmission of farming knowledge from one generation to the next was therefore central to their success. Farming made perfect sense. Establishing a reliable source of food that did not depend on large amounts of travel or access to remote resources. It could provide not only enough food for a small community, but also a surplus to be stored or perhaps traded, opening the door to new and potentially exotic resources.

However, farming could also be risky, and many things could devastate a Neolithic farm. Bad weather and disease were perhaps the most obvious threats and Neolithic people had a very limited toolkit to resolve major problems. The avoidance of such problems, therefore, must have been key, and it was this type of knowledge that was central to a community’s survival. Farmers had to be able to predict when things like the first and last frost might occur, to know when it was safe to plant crops and when might be a good time to move livestock from one location to another. Failure to get such major decisions right could easily have led to disaster. Soils had to be cultivated and fertilised with the addition of compostable materials such as seaweed and animal dung. Failure to correctly manage the fertility of soil could lead to many problems, such as reduced yields or even the proliferation of plant pathogens and pests.

The Mesolithic inhabitants of Ireland had relied on a very different sort of knowledge about where and when wild food might be available. It can be argued that such people exploited a wider range of resources to make them less dependent on a single crop and therefore not as vulnerable to a singular bad event. It cannot be known for certain precisely how these crucial pieces of information were passed on or how each generation learned from the last, but it is reasonable to surmise that this type of knowledge was so crucially important that education must have been a high priority. Some of this information can be seen as being encoded into the landscape in many of the monumental structures built at this time.

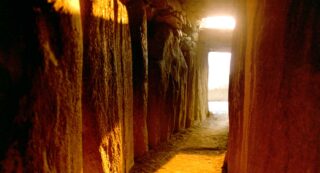

Megalithic Tombs: Newgrange, c. 3200 BC

The Neolithic burial-tomb tradition represents perhaps the most striking series of monument types in Irish prehistory. Some, such as Newgrange, Co. Meath, built around 3200 BC, are among the oldest standing structures in Europe and were central to Neolithic people’s worldview. Many such monuments were built on astronomical alignments, giving rise, for example, to the famous midwinter sunrise at Newgrange. Such astronomic events are clearly linked to seasonal knowledge that was crucial to the timing of crops. These monuments were also, however, much more than giant calendars and are likely to represent some enormous ritual, spiritual and territorial expression in the landscape. Much is communicated through them.

One such example can be seen in the megalithic art preserved at these same tomb complexes. Beautifully executed pecked carvings of spirals and chevrons, along with many other abstract representations, would surely have carried huge significance in the past, and particular knowledge and skills must have been required to produce such works of art.

It cannot be said with any certainty what these works of art represent, but their presence in highly important sites such as passage tombs raises questions about the knowledge they may have conferred. Was their educational value controlled or did everyone have access to the information they possessed? It is very possible they were only accessible to an elite that would seem to have emerged as Neolithic society became more established.

New DNA evidence from the Irish Neolithic seems to support the idea of a strong social hierarchy at this time. Perhaps elite members of society or their inner circle limited access to this crucial information and any other knowledge as part of their own mechanisms of power, which were so central to the community’s success. There appears to be a preoccupation with the transmission of information across generations. These monuments are remarkable feats of engineering and show a determined collective endeavour to establish permanent marks on the landscape that served to transmit key ideas across the generations.

The Bronze Age

2400–500 BC

Associated Sites: Dún Aonghasa, Inis Mór, Co. Galway, Mooghaun Hillfort, Co. Clare, Rathgall Hillfort, Co. Wicklow, Beltany, Co. Donegal and the Hill of Tara, Co. Meath

The arrival of metalworking technology in Ireland marks the beginning of the Bronze Age and is associated with the continuation of many trends that have been seen before. Farming continued but new and improved tools made work more efficient. This era witnessed the ever-increasing specialisation of skills and crafts, evidenced in an abundance of gold objects made with exceptional skill, precision and technical ability.

Some works are clearly the product of many generations of learning and the transmission of detailed knowledge. Minerals such as copper and tin first had to be located, mined and refined through smelting. These materials were sometimes traded over very long distances, as tin was very rare but crucial to the production of bronze. Furnaces and crucibles had to be produced and moulds fashioned. The right fuel, such as charcoal, had to be prepared and the correct mixture of metals and temperatures achieved to pour liquid bronze and cast it into an object like an axe or sword. As a result, such objects were extremely valuable and of high status, and it is very possible that their production was seen as almost magical. The truth behind the process was perhaps only fully understood by a select group.

The Bronze Age is when we see a complex economy really start to develop. Trade, the production of metals and the resulting increased specialisation and quality of tools allowed the development of much more precise carpentry and other crafts, such as textiles and ceramics. Every such trade or craft is again the product of the acquired knowledge of the previous generations and, again, we can only guess at how exactly this knowledge was transmitted. It is likely that these skills ultimately proliferated through apprenticeships over many years, possibly in family lines.

Many sites used in the Neolithic, such as passage tombs, remained as very prominent places in the landscape and were sometimes used or repurposed by Bronze Age and later peoples. It is, however, the hillforts around the country that were constructed between 1200 and 900 BC at places like Dún Aonghasa on Inis Mór, Co. Galway, Mooghaun in Co. Clare and Rathgall in Co. Wicklow, or the great prehistoric landscape of the Hill of Tara in Co. Meath, that are some of the greatest expressions of Bronze Age civilisation seen in the landscape today. Such sites are incredibly complex places, with many periods of time represented in the surviving monuments. However, it is clear that these sites were central to the ever-increasing complexity of Bronze Age economy and society.

The Iron Age

500BC–400AD

Associated Sites: Corlea, Co. Longford, Rathcroghan, Co. Roscommon, Hill of Tara, Co. Meath, Turon Stone, Co. Galway and Castlestrange Stone, Co. Roscommon

The arrival of ironworking technology brought with it many advantages and challenges. The abundance of this new commodity perhaps led to large-scale economic changes in prehistoric society. Less activity is seen across this period in Ireland than one might expect. While the building of many new monuments on the scale of the passage tombs or hillforts is not witnessed, the continued repurposing of these older sites demonstrates that the importance and prestige previously attached to such places had probably not diminished. This trend of repurposing prehistoric monuments to lend contemporary legitimacy continued right through the Iron Age and well into the medieval period. It was perhaps best demonstrated at the ancient provincial royal centres such as Rathcroghan, Co. Roscommon. Similar to the Hill of Tara, Co. Meath, these sites are a complex tapestry of ancient monuments that served as great centres of Iron Age power and early traditions of Gaelic kingship.

The Iron Age was also a time of great trade, both domestically and internationally. Roadways were built to facilitate the movement of wheeled carts and their cargo through rough terrain such as those discovered at Corlea, Co. Longford, dated to 147 BC, and many other bogs throughout the midlands. These roadways are part of a complex network of internal trade moving through landscapes often dominated by the imposing monuments of previous centuries.

The height of Roman expansion in the late Iron Age famously never encompassed this island. Ireland did not, however, exist for many centuries in isolation from the Roman world and, although rare, imported goods have been found associated with many high-status sites that could only have come to Ireland through contact with the Roman world. This aspect of Iron Age Ireland is still very unclear but continued research into this topic will no doubt shed further light on it. The myriad ways in which Iron Age Ireland has been influenced by trade and contact with Europe is, however, clear. This influence was expressed through developments in art, language and culture, if not the abundance of its monumental architecture. The development of Celtic styles of art, a phenomenon very much associated with Ireland but part of a much wider European tradition, is seen from this period. The stone at Castlestrange, Co. Roscommon and the Turoe Stone in Co. Galway are two of the finest examples of such art visible in the landscape today. Both are spectacularly carved boulders covered in La Tène-style designs.

The Irish language itself probably also arrived here during the Iron Age. Ultimately the Christianisation of Ireland through contact with the Romanised world would bring about the most substantial changes in the Irish tradition of education, with the introduction of the written word and the end of prehistory.

The study of prehistoric Ireland allows us to understand a great deal about how people have always learned from each other. People’s knowledge of the natural world allowed communities to thrive before farming, and the knowledge of farming later facilitated the settling of the land, the expansion of the population and the development of many new crafts and skills. Contact with the rest of Europe has always facilitated the importation of new ideas and cultures, which so often have grown to define the inhabitants of this island as a people. New ways of life came and went. Technology more than once revolutionised daily life and whole social structures. Ever-increasing trade was seen across communities, while great expressions of power occasioned the monumental architecture that still dominates the landscape. This all stands as a testament to the value and importance placed on education as something central to the continued success of any society.