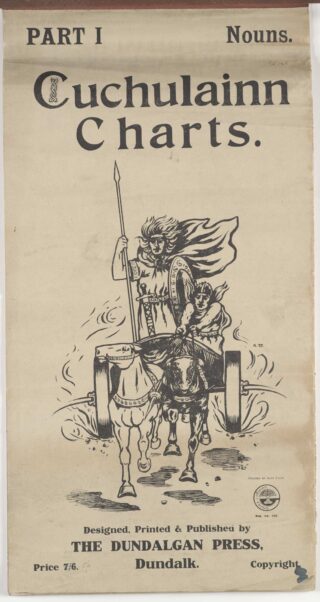

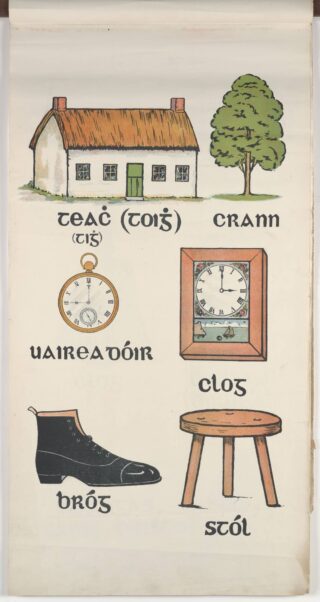

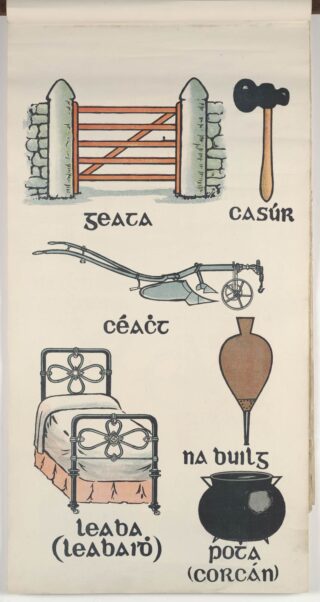

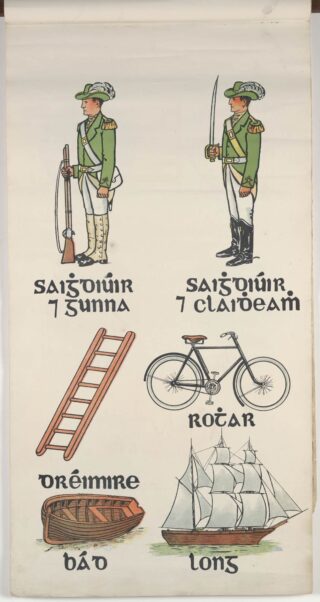

In teaching Irish, Pearse championed what he referred to as the An Modh Direach. This was based on the ‘Direct Method’, a visual system of language teaching which he had earlier seen used in Belgian schools. Pearse also encouraged his pupils to learn Irish through conversation, and his aim was to make it the everyday language of the school. Pearse and his teachers used the Cucuilainn Charts and text book produced by the Dundealgan Press as an aid to teaching Irish in the school.

Pearse wrote in the school prospectus about the care that had been taken with the decoration of the school and the ‘carefully considered scheme of colouring and design’. His aim was to encourage in the boys ‘a love of comely surroundings and the formation of their taste in art. In the classrooms beautiful pictures, statuary, and plants replace the charts and other paraphernalia of the ordinary schoolroom.’ Pearse’s brother William joined the school as the art teacher. William also played a key role in staging and directing the school’s theatrical productions. As the years progressed, and Patrick became more and more caught up in revolutionary politics, William took on a lot more responsibility for the practical running of the school.

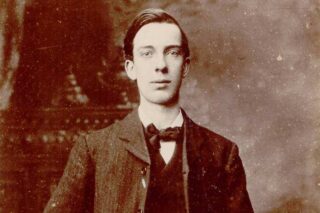

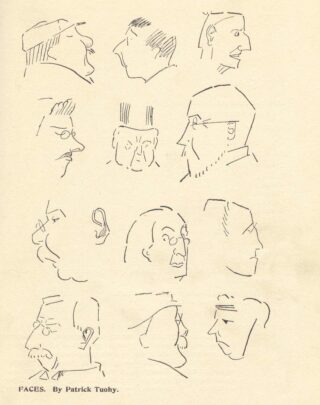

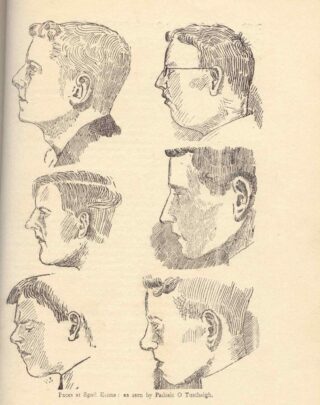

Among William Pearse’s pupils in the early years of the school was Patrick Tuohy. Tuohy would later become one of the leading Irish artists of his generation and some of the caricatures he drew of his teachers and fellow pupils appeared in the school magazine, An Macaomh

Pearse said the school would take inspiration from the ancient Gaelic tradition of fosterage, when a young boy would be raised and taught by a neighbouring clan. The involvement of his family was a key part of Pearse’s vision for Scoil Éanna. In addition to his brother William’s role as art master, his sister Mary Brigid taught music while his other sister, Margaret, was an assistant mistress. His mother acted as housekeeper. A former pupil, Kenneth Reddin, later remarked upon how un-institutional the school felt and he attributed this to the fact that women had charge of the domestic arrangements. Pearse emphasised his mother and sister’s involvement in the School Prospectus, and suggesting that ‘in conjunction with its private character this made it specially suited for the education of sensitive and delicate boys’

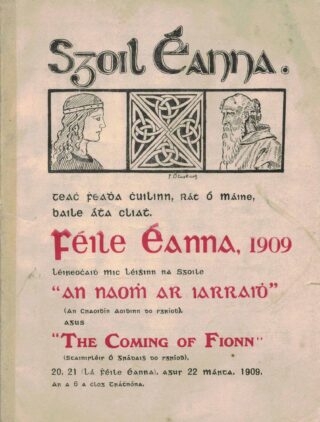

The school quickly developed a reputation for the quality and the innovation of their theatrical performances. On 22 March 1909 the boys performed An Naomh ar Iarraidh (‘The Lost Saint’) by Douglas Hyde in the theatre of Cullenswood House as part of a double bill with The Coming of Fionn by Standish O’Grady. Among the audience was the academic Stephen Gwynn, Edward Martyn, Padraic Colum, Eoin MacNeill, Mary Hayden, Mr. & Mrs. Don Piatt, Count and Countess Markievicz, Agnes O Farelly, Sir John Rhys, W. B. Yeats and Standish O’Grady, who was accompanied by his wife. The performance took place in a little corrugated iron shed in the grounds where a stage had been erected.

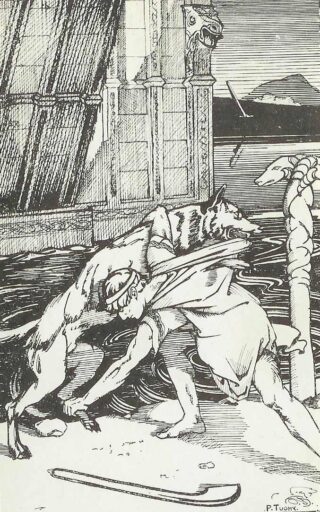

The heroes of the ancient Irish sagas, such as Fionn Mac Cumhail and Cúchulainn, were presented as role models to the boys of Scoil Éanna. Pearse saw the school as being in the tradition of the ancient Boy-corps of Eamhain-Macha in which the young Cúchulainn had been raised and educated. In that tradition children were brought together ‘in some pleasant place under the fosterage of some man famous among his people for his greatness of heart, for his wisdom, for his skill in some gracious craft’. A former pupil from Scoil Éanna remarked that Cúchulainn was mentioned so often in the school it was as if he was ‘an important but invisible member of staff’!

These images of Cúchulainn were drawn in the 1920s by Patrick Tuohy for an edition of Standish O’Grady’s novels entitled The Coming of Cuchulain and In the Gates of the North published by the Talbot Press.

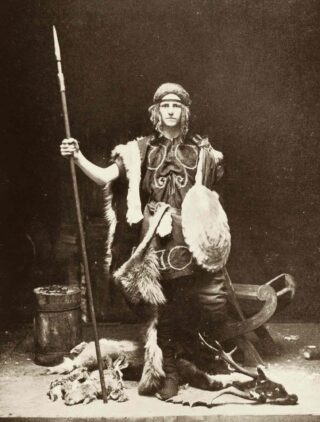

To mark the end of the school’s first year in 1909, Pearse wrote an elaborate pageant entitled Mac-Ghniomharta Cúchulainn (‘The Boy-deeds of Cúchulainn’). Pearse said that he hoped it

‘would crown our first year’s work with something worthy and symbolic; anxious to send our boys home with the knightly image of Cuchulainn in their hearts and his knightly words ringing in their ears. They will leave St. Enda’s under the spell of the magic of their most beloved hero, the Macaomh who is after all the greatest figure in the epic of their country, indeed as I think the greatest epic of the world’

Frank Dowling is photographed here in costume playing the title role.

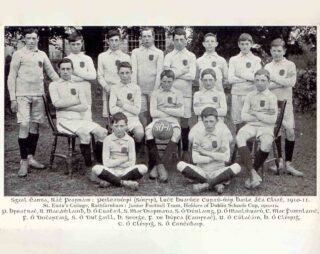

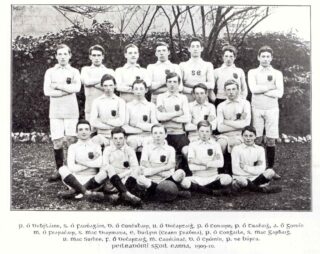

Writing in An Macaomh in December 1909 Pearse spoke about his pleasure at the success of the school s athletic teams ‘our boys must now be among the best hurlers and footballers in Ireland. Wellington is credited with the dictum that the battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton. I am certain that when it comes to a question of Ireland winning battles, her main reliance must be on her hurlers. To your camáns, O boys of Banba!’

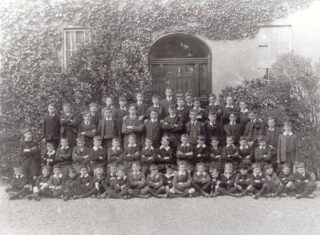

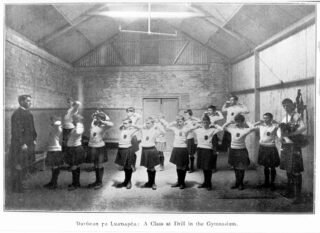

Drill and physical education played a central role in the school’s curriculum. The boys in this picture taken in 1909 wear kilts, an optional school uniform which, according to the school prospectus, provided ‘an economical, hygenic, and becoming costume for boys’.

Some years after this photo was taken, Con Colbert, who would later be executed for his part in the 1916 Rising, became Physical Education master and introduced the Swedish Method, a more militarised approach to exercise in school with an emphasis on discipline, marching and military drill.

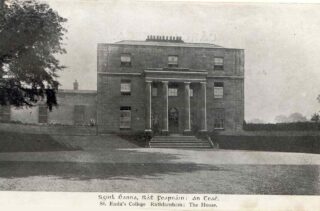

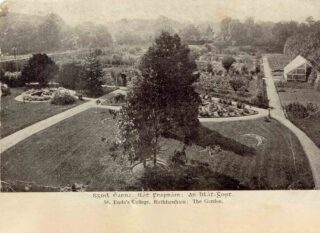

Pearse identified nature study and physical science as an ‘essential part of the work at St. Enda’s’. In 1910 he moved his school from suburban Rathmines to the foothills of the Dublin mountains in Rathfarnham in the belief that it would provide ‘scope for that outdoor life, that intercourse with the wild things of the woods and the wastes … [that] ought to play so large a part in the education of a boy.’

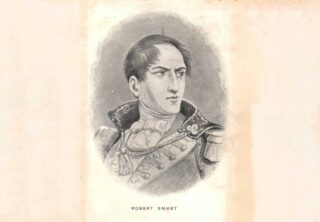

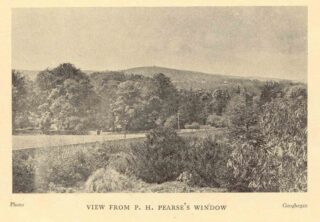

Pearse’s decision to relocate his school to what is now the Pearse Museum and St. Enda’s Park in Rathfarnham was also motivated by the property’s association with the revolutionary Robert Emmet. Emmet is said to have frequently walked in the grounds in secret with his sweetheart, Sarah Curran, in the early 1800s. Pearse hoped that these historic associations would help his pupils to connect with the past and draw inspiration from it. He described the property’s connection with Emmet in the 1910 edition of the school magazine:

We know that Emmet walked underneath these trees (some of them were already old when with bent head he passed beneath their branches up the walk, tapping the ground with his cane as was his wont); he must often have sat in this room where I now sit, and, lifting his eyes, have seen that mountain as I see it now (it is Kilmashogue, amid whose bracken he was to crouch the night the soldiers were in Butterfield House), bathed in a purple haze as the yellow wintry sun sets, while Tibraddon has grown dark behind it. I do not think that a house could have a richer memory to treasure, or a school a finer inspiration, than that of that quiet figure with his eyes on Kilmashogue.

Pupils and teachers at Pearse’s school were encouraged to use the extensive grounds of what is now St. Enda’s Park to observe and learn about the natural world at first hand. Pearse wrote that ‘f our boys observe their fellow-citizens of the grass and woods and water as wisely and as lovingly as they should, I think they will learn much’

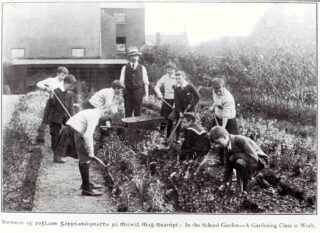

Boys were first introduced to the natural world in the school garden where they were taught ‘Practical Gardening and Elementary Agriculture’ by Mícheál Mac Ruadhrí, a native Irish-speaking gardener who was also a prize-winning and much respected traditional story-teller. Any boy who wished it was allotted a plot of ground which they were ‘at liberty to plan out and cultivate according to his own taste’.

The school also had a museum which contained ‘zoological, botanical, and geological specimens, together with some illustrations of industrial processes and a few objects of historical and antiquarian interest’. It was cared for by a curator elected from amongst the student body. Many of these specimens came from the pupils themselves and the school magazine recorded donations by the boys of seashells, butterflies, dragon flies and saw-flies. All the specimens in the museum had to have met a natural end as the boys were under a solemn ‘geasa’, or obligation, not to kill ‘wild things’.

Pearse regularly held an Aeridheacht or ‘Open Day’ at the school to promote Scoil Éanna. These events attracted many leading cultural figures to the school. This photograph was taken of those who attended an Aeridheacht c. 1914. Among the group were Douglas Hyde, Eoin Mac Neill, Agnes O Farrelly and Eamonn Ceannt. The second photograph shows an open-air pageant performed on that occasion, Fionn: A Dramatic Spectacle. Pearse took advantage of the beautiful location of his school in the foothills of the Dublin Mountains to provide a dramatic backdrop for the school’s productions

Both Patrick and Wiliam Pearse would later be executed for their role in the 1916 Rising.

Although Scoil Éanna continued until 1935 under the leadership of Pearse‘s mother and sister, in many ways much of what was innovative and exciting about the school died with them. However there is much we can still learn from Patrick Pearse’s emphasis on providing children with an education which nurtures their talents and recognises their individuality. Pearse’s educational legacy is perhaps best expressed in his poem, ‘I have not garnered gold’

Of riches or of store

I shall not leave behind me

(Yet I deem it, O God, sufficient)

But my name in the heart of a child.

If you want to find out more about Pearse and his educational work, why not visit the Pearse Museum and explore our exhibition ‘Who is Pearse?’