Ireland’s introduction of the continental orders of the Cistercians and Augustinians was instrumental in bringing about radical changes in Irish ecclesiastical building practices. One highly significant development to Irish architecture that came about as a result of these changes was the introduction of the Gothic arch. Another was a new style of sculpture that emerged on late-Romanesque churches west of the River Shannon during the first half of the thirteenth century, representing a fusion or even conflict between the introduced Cistercian architecture and the vernacular Hiberno-Romanesque style. Architect and pioneering architectural historian Harold Leask called it the “School of the West”. Leask was the inspector of National Monuments between 1932 and 1949 and completed a three-volume study, Irish Churches and Monastic Buildings, in 1960, in which he introduced the world to his theory.

He gave the name to a group of churches built in the west of Ireland that share an assemblage of specific architectural features and characteristics seldom found elsewhere in Ireland and within a defined space of time. Leask suggested that the so-called “school” was a body of tradition that found expression in a geographically and chronologically defined group of buildings in the ancient kingdoms of Connacht and Thomond, the majority of which were erected as parts of monastic settlements. The school can be entirely defined in terms of decorative traits rather than of structure or design. But a clear, discernible movement of a group of local stone-carvers, masons and sculptors under the guidance of a master can be identified among the School of the West sites. Whatever form the school took, there was a clear mechanism for the transmission of artistic skill and knowledge within this local group of stonemasons, who demonstrated an exceptional standard of sculpture and stone-carving and produced some of the most highly ornamented buildings in the west of Ireland. Some of the earliest work of the school can be seen at the late-twelfth-century Cistercian houses of Corcomroe, Co. Clare and Boyle, Co. Roscommon. However, its flourishing is not witnessed until the dawn of the thirteenth century, when it reached maturity in the Augustinian houses of Ballintober and Cong in Co. Mayo, before making its final appearance in the church at Drumacoo, Co. Galway.

The school’s sculptural tradition is demonstrated in monastic communities that belonged to a network of royal patronage involving high-powered individuals in church and state. Kings and nobles lavishly indulged in the building of large monastic houses in a bid to maintain their high status, to influence political relationships within their kingdoms or to strengthen their position in the highly competitive political environment of medieval Ireland. These dynastic ambitions are expressed in some of the most superb examples of medieval stone sculpture, the undertaking of which was nothing short of monumental.

The particular impact of the Cistercian order on Irish architecture cannot be underestimated. For example, the tradition of monumental stone building was not witnessed in the Irish landscape before the arrival of the Cistercians, yet by the opening years of the thirteenth century there was hardly a corner of Ireland into which the Cistercians had not penetrated. However, there existed a clash between ancient values and traditions of art and the strict discipline of the order. Indeed, the dynamic repertoire of rich ornament that characterises the style of the School of the West is in direct conflict with the Cistercian philosophy, in which monasteries and churches were designed to be simple, utilitarian and devoid of inessential embellishment in an effort to avoid distraction from prayer and reflection. While the architecture of many Cistercian foundations throughout Ireland reflects their desire for austerity and purity as well as their disapproval of ornament, those in the west, farthest removed from English influence, noticeably rebelled against it, producing a unique blend of flamboyant stone carving in an often plain, austere setting. The result was the creation of some of the school’s most adventurous, innovative sculpture, executed to perfection.

The School of the West masonic artists produced sculpture in a consistent and distinctive style, excelling in the concentration of characteristic ornamental design that appears particularly upon capitals, corbels, doorways and chancel arches on ecclesiastical buildings, though less frequently on their windows, all of which suggests some fusion of Romanesque and Gothic. Various architectural elements are seen as defining features of the school, including vaults and piers and the complete framing of window openings with mouldings. Often of a high quality and likely inspired by English and French models, the sculpture is well modelled in relief, varying from semi-naturalistic to wonderfully stylised plant ornament. Curious animal motifs and deeply undercut chevron or geometric ornament are other hallmarks of the school. There are also certain features that typify the transitional aspect of the style in which the School of the West is renowned. Best illustrating this transition are the use of both round and pointed arches alongside each other, as seen in the west end of the nave at Boyle, Co. Roscommon, and the use of chevrons and Romanesque-style beasts on a pointed-arched doorway, as seen at Drumacoo, Co. Galway. The execution of the School of the West style is testament to the remarkable quality of the masons’ workmanship, revealing their deep understanding of art, sculpture, geology, geometry and engineering.

The increasing sophistication of architectural design, sculpture and ornament, as well as the technical demands of a style that required a combination of energy and precision, made building an increasingly technical operation. Yet these developments enhanced the status of the professional craftsmen, whose work and expertise was frequently recognised, admired and in constant demand. Selecting a master mason was a decisive moment for a patron in the building of the religious house that would become his legacy. Not only was the mason required to supervise a potentially large team, he was also tasked with procuring stone, working out dimensions and plans, preparing templates and erecting the scaffolding, cranes and pulleys needed for lifting stone. Indeed, the accomplishment of this diverse range of responsibilities to a high standard would ensure a thoroughly professional building operation and the guarantee of future work. The masons’ outstanding engineering and artistic achievements as seen in the religious houses that typify the School of the West style are testament to the professional calibre of local Irish craftsmen. Such creative skills were seldom seen since the era of the iconic high crosses of the ninth to twelfth centuries.

Abbeyknockmoy, Co. Galway, c. 1190

Generous local patronage from the O’Conor kings of Connacht allowed for the expansion of Cistercianism to the plains of north-eastern Co. Galway at Abbeyknockmoy. The O’Conors were notable patrons of the arts and the church and used their patronage as a mechanism to display their self-confidence as powerful and wealthy royal leaders. Following the death of Cathal Croibhdhearg in 1224, who had retired to Abbeyknockmoy to become a monk, the abbey became a mausoleum for several generations of the O’Conor family.

Built according to the standard Cistercian pan-European tradition in the twelfth century of vaulted presbyteries and transeptal chapels, the majority of Abbeyknockmoy’s extensive buildings date from the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, with further building work carried out in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Thus they represent a diverse variety of architectural styles. Parallels with Boyle Abbey are particularly strong at Abbeyknockmoy and it appears that the group of sculptors who worked here can be identified as the same as those who worked in Boyle, who had a major influence in the development of the School of the West style. The surviving remains consist of the church and both the eastern and southern ranges of the claustral buildings. The chapter house has a triple east window with a single window of later date on either side. It was divided into three barrel-vaulted chambers in the fifteenth century, which now obscure the east window.

Abbeyknockmoy was the first Irish ecclesiastical site to employ ribbed vaulting. The north wall of the rib-vaulted presbytery in the chancel possesses decorative corbel shafts ornamented with leaf and foliage motifs, while the capitals, sitting above triple colonettes, display scallops with delicate foliage, lilies and triskeles in the shields. The exterior of the windows in the chancel are continuously framed, with hood-mouldings above the arches, featuring carved ornamentation including lilies, cylinders and incised circles. The centre window is decorated with a row of half-palmettes and human masks on either side of the ends. Though the nave arcades are more or less featureless, the third pier of the south arcade includes a fine example of a sculptured royal head with curly hair and large eyes adorned with a crown, possibly representing Cathal Croibhdhearg O’Conor, as a tribute to his patronage. Also displayed in the north arcade of the nave is the round head of a beast with bared teeth. This is clearly the work of the School of the West masons and the influence of the carved decoration of Boyle Abbey can be seen in the richly carved chancel arch, although this carving is not as fine as those at Boyle. Some distinctive chevron ornament is found in the chapter house, similar to that found at Corcomroe. While the masons at Abbeyknockmoy seem to have emulated the work at Boyle Abbey, it appears that the mason who constructed the Abbeyknockmoy vault was also employed at Ballintober, Co. Mayo.

Corcomroe Abbey, Co. Clare, c. 1198

Founded by the O’Brien Kings of Thomond in the late twelfth century, the Cistercian abbey of Corcomroe is nestled in a fertile valley amidst the karst landscape of the Burren in north Co. Clare. It appears that its builders were inspired by the earlier Cistercian foundation at Abbeyknockmoy in Co. Galway, as its eastern façade is almost identical to that at Corcomroe. The church at Corcomroe bears witness to some of the most remarkable execution of the School of the West in its many fine sculptural features, including the mouldings, capitals and bases of the transepts and the fine rib-vaulted presbytery.

The quality of the limestone masonry and exceptional carving compensate for the unusually reduced scale of the cruciform church. Some of the school’s earliest examples of low-relief naturalistic botanical carvings, including lilies, poppies, foxgloves and deadly nightshade, comprise the ornament on a number of the capitals and corbels at the northern end of the church in the presbytery, while the capitals of the south transept chapel bear fine figure sculpture of human heads. This artistic range and the delicate herring-bone and chevron ribbing of the vault of the presbytery are a clear rebellion against the strict discipline of the Cistercian order, which required simplicity in their churches.

The embellishment continues within the presbytery in the sedilia, the ornamental seats used by the clergy when officiating at mass. Its capitals are decorated with palm motifs, classic early thirteenth-century carving typical of the School of the West. In the wall above, a low-relief effigy of a bishop is set within an architectural canopy. On its external angles, curious biting beasts with long snouts and clawed paws show striking similarity to the lively repertoire of ornament on the late-Romanesque doorway at Killaloe Cathedral, Co. Clare, which can be seen as a decisive component in the development of the school during the early thirteenth century. It was perhaps this doorway that inspired the school’s masons, as many of its details are repeated at Boyle, Ballintubber and Cong. The adjoining chapels on either side of the presbytery are equally ornamented, with delicate bluebells and fleurs-de-lis.

Boyle Abbey, Co. Roscommon, c. 1161–1218

Boyle Abbey is perhaps the prime example of what is arguably the essence of the School of the West and an outstanding example of Romanesque architecture in Ireland. Possibly built on the site of an earlier monastery, the abbey was founded in 1161 and completed c. 1218 under the patronage of the McDermots of Moylurg. One of the largest and most complete abbeys of the Cistercian order in Ireland and also their earliest foundation in Connacht, it was built as a daughter house of Mellifont Abbey in Co. Louth. The present ornamental remains are the result of a sequence of stone carving that produced a diverse blend of architectural and sculptural styles and traditions that thoroughly highlights the work and skill of the accomplished School of the West craftsmen over a period of approximately 50 years. Although typically Cistercian in plan, there are some deviations in design – unlike most other Cistercian churches, Boyle also had a crossing tower. Other peculiarities are probably most conspicuous in the nave, where a number of distinct phases can be observed. For example, the southern elevation displays round arches, while those in the northern arcade are pointed.

The present remains consist of a presbytery flanked by two chapels in each transept, an incomplete nave with eight bays, a crossing tower and a north aisle, while to the south are other buildings including the dormitory, kitchens and refectory. Little, however, survives of the claustral buildings and nothing remains of the cloister arcades.

Boyle Abbey was instrumental in the development of Romanesque style and technique west of the Shannon, but much of its finest decoration, especially the animal and human figure designs, are largely in the more ornate and unique Hiberno-Romanesque style that exhibits a distinctly Celtic flavour. The detail of this carved ornament has a vivacious quality generally not paralleled elsewhere. The earliest of this ornamental carving at Boyle can be seen at the eastern end of the church, the most striking of which is a remarkable low-relief carving of bird’s head on the sedilia that closely resembles the precise carving on the west doorway of the Nun’s Church at Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, dated to c. 1167. This suggests that the same mason worked at both locations, using the River Shannon and its tributaries as a means of transport between the two sites. Most of the early work at Boyle consists of an assortment of acanthus-like foliage and scalloped ornament, the latter displayed in the capitals of the crossing and also seen in the presbytery at Abbeyknockmoy. The three capitals on either side of the chancel arch are decorated with upright leaves, split scallops and delicately defined foliage, while a frieze of scallops links the arches of the two chapels of the north transept, both of which are adorned with scallop and foliate motifs.

A sculptor dubbed the “Ballintober Master” completed the greater part of the stone carving at Boyle, where his ornament and design combined local characteristics with a knowledge of a more cosmopolitan Romanesque style, drawing on influences from England and continental Europe. Some of his best work is demonstrated on the capitals of the last four bays of the nave and the corbels inserted in the spandrels of the arches. Dense patterns of palmette foliage cover the capitals along with a diverse repertoire of meticulously carved blossoms, berries, scallops, birds, animals and human figures in dynamic postures typical of the School of the West. The ornament is dense but never cluttered. The complex compositions of brilliantly executed squabbling dog and chicken motifs on capitals in the south arcade, along with painstakingly carved human figures standing upright between leaf- and grape-laden trees on a capital in the south arcade and intertwined dragons on a corbel in the western bay, are some of the most outstanding works of Irish Romanesque, executed with ultimate precision, vigour and depth. The “Ballintober Master” was probably employed at Ballintober Abbey between 1216 and 1225, but his work is also demonstrated at Abbeyknockmoy, a daughter house of Boyle, and most notably at Cong, Co. Mayo.

Boyle’s sizeable dimensions and the wealth of sculpture witnessed throughout the building are unparalleled among Cistercian foundations in the west of Ireland. Indeed, no other church displays such an abundance of sculpture and it was Boyle that was most influential in developing the broad range of corresponding motifs and characteristic ornament of the School of the West.

Ballintober Abbey, Co. Mayo, c. 1216

It was for the Augustinians that the King of Connacht, Cathal Croibhdhearg O’Conor, founded the elegant abbey of Ballintober in 1216. According to tradition, mass has been said here regularly without a break since the year of its foundation. The cruciform church and cloisters appear to have been borrowed from the typical Cistercian ground plan, with east chapels in the vaulted transepts and a vaulted presbytery, but its absence of aisles is notable. The flat-ended east wall with its three windows is also reminiscent of Cistercian architecture. The vaulting at Ballintober uses the same system of jointed masonry in place of a keystone, as seen at Abbeyknockmoy, but is more accomplished here. Having worked previously at Abbeyknockmoy and Boyle Abbey, the School of the West masonic artists appear to have moved to Ballintober, where their characteristic style of decoration has been applied in the chancel and at the crossing or space that coincides with the transept. This area contains some of the best examples of the school’s sculptural skills.

The somewhat austere character of much of the building contrasts starkly with the range of lively artistic sculpture seen in some of the chief architectural elements of the church, the ornament of which shows a great concern with symmetry. The details of the windows, doorways, capitals and mouldings are typical of the School of the West. The three lancet windows in the east wall are completely framed in mouldings, richly sculpted on the exterior with animal, foliate and chevron ornament. Inside, the windows are also framed with continuous round half-columns, while inward-facing dragon heads grow from the top of each column, each with a snake protruding from its jaws. The dragons appear to bite grimacing animal masks, which have snakes protruding from either side of their mouths. The intricately carved capitals of the chapter house doorway appear to have been inspired from those at Inishmaine, their ornament comprising trees, florals, branching foliage and triskeles, while the capitals of the chancel feature birds, foliage, dragons and beasts with interlocking necks in late-Romanesque style. Set into the south wall of the north chapel, a decorated corbel is carved with a human head with slightly waving hair, drawn back behind its large ears. Close architectural links can be also identified between Boyle and Ballintober, especially in the corbels at the crossing and in the chancel arch.

It has been suggested that these expert creations are the work of the skilled School of the West mason, the “Ballintober Master,” whose skills are also witnessed at Boyle, but the composition and execution appear to have matured at Ballintober. His work is bold, vigorous and executed in high relief, reflecting an ultimate self-confidence. Indeed, the depth of the carving seen at Ballintober is more than what is demonstrated at Boyle, illustrating a development and progression in this craftsman’s work.

Inishmaine Abbey, Co. Mayo, c. 1220

Only 15 miles north of Ballintober, the early thirteenth-century Augustinian abbey of Inishmaine lies on the shores of Lough Mask in Co. Mayo on an early monastic site founded in the seventh century by St Corbmac. The church is small, with a nave, chancel and north and south chambers that create a T-plan.

In terms of both mouldings and decoration, many comparisons can be made between Inishmaine and other School of the West churches. The capitals of the chancel arches are intricately adorned with fighting beasts with barred teeth, one biting the nose of the other, dragons with curling tails, lilies, stylised foliage, interlaced reeded stems and triskeles. Some of this low-relief ornament is very close in motif to the slype doorway at Cong and the capitals of the chapter house doorway at Ballintober. The pair of narrow, round-topped windows in the east wall of the chancel are framed on the exterior in continuous rolls in typical School of the West fashion. A crude carving of a small figure on a bridled horse with a long sinuous body and arched neck adorns one side of the windows, while a bird with a long tail, pursued by a grotesque beast with bared teeth, adorns the other.

Cong Abbey, Co. Mayo, c. 1226

Situated between Lough Corrib and Lough Mask, the Augustinian abbey of Cong was founded in the twelfth century by king of connacht and high king of Ireland, Turlough O’Conor, on the site of a seventh-century monastery. This was, however, destroyed in 1203 but was subsequently rebuilt and dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary, with a large portion of the existing remains dating from this time. Some additions exist from the fifteenth century and there is some nineteenth-century restoration. The church comprises a chancel with a tall, triple pointed window, sacristy and nave but no aisles. The abbey witnessed the final flowering of the School of the West and exhibits what are arguably some of the finest examples of early ecclesiastical architecture, sculpture and masonry in Ireland.

Romanesque doors, clustered pillars and delicately carved floral capitals are some of the sculptural highlights of the church at Cong and suggest influences from France. The pointed doorway leading into the chapter house is a fine example of early Gothic architecture, possibly dating to the first two decades of the thirteenth century. Its elaborate ornament, however, is strongly influenced by late-Romanesque style. The rich palmette ornament, chevrons and lines of beading are exquisitely executed, and possibly represent some of the last works of the School of the West. Though not in their original position, the capitals of the north doorway to the church are executed with equal precision, adorned with fine, complex foliate ornament, hanging acanthus leaves with scalloped edges, reeded stems, lozenges and vine-scrolls in low relief. The slype doorway is similarly ornamented with a complex range of delicate carving, including chevron, lozenge, berry, foliate and palmette motifs.

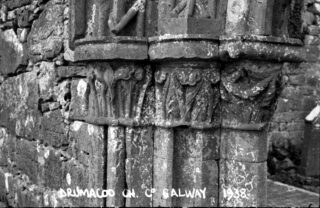

Drumacoo Church, Co. Galway, c. 1235

Built on the site of an early monastic settlement founded in the sixth century by Sárnait or St Sourney, the original rectangular parish church with its plain lintelled doorway was extended in the early thirteenth century, and the majority of the present remains date from that period. A Gothic-revival-style mausoleum for the St George family of Tyrone House was built against its north wall in 1830. The sculpture throughout the church is of remarkably high quality, with exquisite detail and three-dimensional carving belonging to the latest phase of the School of the West.

During the thirteenth-century extension to the church, a deeply splayed double window framed by a continuous roll was added to the east wall. An elegant, finely carved doorway was also added to the south wall and can be seen as a minor masterpiece of the School of the West. Typical Gothic features, including a pointed arch and the style of its bands and mouldings, are combined with Romanesque chevrons and lozenges, while Romanesque-style foliate patterns and small beast heads dominate the ornament on its capitals. The snarling rounded heads, bulging eyes and upright pointed ears of the beasts appear to emulate typical Hiberno-Romanesque animal sculpture. This fusion perfectly illustrates how the School of the West tradition straddles both Romanesque and Gothic styles. While some of the moulding is reminiscent of Boyle, and the foliate ornament is similar to that at Cong, the appearance of the work at Drumacoo is later, more deeply carved and more advanced, marking the end of the School of the West tradition in Ireland.

One of the great artistic contributions made by the medieval Irish church was the superb sculptural tradition of the School of the West, which created some of the most inventive architectural sculpture of the early thirteenth century in the west of Ireland. The School of the West churches share a wealth of similarities and correlations that demonstrate the movement of local stonemasons between the various sites in the west of Ireland and the subsequent transfer of knowledge between them over a defined period of time. The varied range of iconic motifs with clear Celtic attributes shared by these churches reveals the school’s deep-rooted tradition of Hiberno-Romanesque techniques.

While the Gothic style was rapidly developing in contemporary Europe, the Hiberno-Romanesque tradition still continued in Ireland. Though the Cistercians of the west of Ireland were deeply rooted in vernacular architecture, the exposure to diverse artistic landscapes that was offered by the pan-European network of the Cistercian order facilitated the spread of some outside influences to the west, which eventually seeped through into its architecture. Thus, the churches of the School of the West represent the last expressions of Romanesque in both Ireland and Europe, before Ireland’s cautious adoption of the first phases of Gothic style.

The School of the West tradition boldly continued in Connacht until about 1228, when building activity came to an abrupt end before the Anglo-Norman invasion of the region in 1235. Entries in the Annals of Connacht and the Annals of Lough Cé suggest a mass exodus of skilled craftsmen from Connacht to “far foreign regions” in 1228, possibly owing to the internecine squabbles of the O’Conors. During this period Ireland was entering into a time of increasing conflict, with determined invasions into distant provinces, rapidly followed by crushing defeats. Such an antagonistic environment did not encourage a continuance of artistic traditions. Furthermore, the eventual effects of the Anglo-Norman invasion compounded this problem and effectively heralded the end of the School of the West, resulting in a long interruption in Gaelic masonic craft that was not revived until after the Black Death in the early fifteenth century.

Today, the religious houses that embody the great artistic achievements of the School of the West still remain on the Irish landscape. Their ruins act as a reminder of all that they have endured over the centuries – plunder, war, suppression and destruction. But conservation practices have allowed the architectural and sculptural legacy of these enigmatic stonemasons to live on, and the wonderfully dynamic array of motifs left behind by the hands of these skilled craftsmen showcase some of our most enduring artistic traditions.