In the mid-sixteenth century, there were more than 400 families in Ireland who specialised in medicine, law, poetry, history and music. These were the aos ealadhan – the professional learned classes – who, as eminent skilled professionals, performed multiple functions in Gaelic society. Highly respected, they were accorded a position of privilege at the courts of the Gaelic ruling dynasties and were rewarded with hereditary tenure of lands and other forms of wealth for their services.

However, with the conquest of Ireland that followed the Battle of Kinsale in the early seventeenth century, many of the traditional Gaelic institutions and disciplines had little or no relevance in an anglicised world and were abolished under English rule. This collapse of the Gaelic order, and with it the patronage of the ruling families, inevitably brought about the demise of the Gaelic professions.

Today, however, surviving monuments and manuscripts offer a glimpse into the Gaelic medieval arts and seats of learning and the world of the hereditary learned families and their patrons, revealing the physical environments in which these families lived and taught.

The Book of Hy-Brasil: A Medical Masterpiece

Associated Site: Aughanure Castle, Co. Galway

Hereditary practitioners of professional medicine served the ruling Gaelic dynasties between the twelfth and seventeenth centuries. The hereditary aspect of a particular discipline was a distinctive organisational feature of the Gaelic learned tradition. Lawyers, poets, historians and musicians also adhered to the same principle.

The practice of medicine was the preserve of a select number of learned families over successive generations. They were responsible for the organisation and regulation of medical schools, the practical training of students and the translation and composition of medical texts for educational and reference purposes. The most renowned text produced by a Gaelic school is the Book of Hy-Brasil or the Book of the O’Lees, compiled during the fifteenth century. These types of medical texts were reference handbooks for practising physicians.

The O’Lees were among the leading Gaelic physicians in Connacht and were the hereditary physicians to the O’Flaherty lords of Iarchonnacht in western Co. Galway, whose chief stronghold was close to the shores of Lough Corrib at Aughnanure Castle. The O’Lees would have held a very dignified position among the lord’s immediate retinue and entourage of learned men and were awarded hereditary tenure of lands free of taxes and tribute for the medical services they rendered.

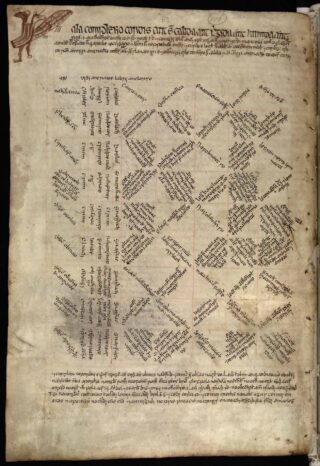

The Book of Hy-Brasil is an Irish-language medical manuscript, translated in 1443 from the Latin treatise Tacuini Aergritundium, which itself was translated in 1281 by Jewish physician Faraj ibn Salim in Sicily from an earlier Arabic text written in eleventh-century Baghdad. This would have made a wealth of new European medical knowledge and techniques available to the O’Lee physicians in Ireland. The large vellum manuscript details the treatment for many diseases of the time. The writing is formed into tables and patterns resembling the astrological symbols of the zodiac, with many highly decorated, illuminated initial letters.

Strange, fantastical creatures adorn the corners of many of the book’s pages and according to legend it possessed magical properties. It was used by Murrough O’Lee in the seventeenth century, who claimed that in 1668 he was mysteriously transported to the enchanted Island of Brasil, somewhere off the west coast of Ireland. Here he received the book and was instructed not to open it until seven years had passed. He did as he was told and, upon opening the book, suddenly acquired a supernatural ability to treat all sorts of human illnesses. Though he never received any training, his abilities were immense and he attributed his newly acquired medical knowledge to his “journey” to the island of Brasil.

The Book of Hy-Brasil is currently held by the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin.

Cahermacnaghten: A School of Legal Learning

Associated Site: Stone cashel and associated schoolhouse, Cahermacnaghten, Co. Clare

The stone fort complex at Cahermacnaghten in the Burren region of north Clare is long associated with the practice and teaching of law. During the sixteenth century successive generations of the O’Davorens, hereditary lawyers to the O’Loughlin chiefs of the Burren, practised their art there and conducted a great literary and law school, of which the celebrated Irish antiquary Dubhaltach MacFhirbhisigh was a student.

Records show that the school was founded by Giolla na Naomh O’Davoren c. 1500 and continued in use well into the seventeenth century as a centre for the study of Fénechas, the system of law commonly known as Brehon law, through which Gaelic medieval society was governed. Archaeological investigations have revealed that a gatehouse and five stone buildings were added within the confines of the early medieval stone enclosure, while the single-storey schoolhouse lay outside to the south-west. This is known as Cabhail Tighe Breac and is where the students gathered for instruction in Latin and Brehon law and where many legal texts were transcribed. The building’s proportions and internal arrangement are typical of a Gaelic schoolhouse, while the recovery of a fragment of inscribed slate, similar to those discovered in medieval and Renaissance schools across Europe, is a further testament to its scholarly function.

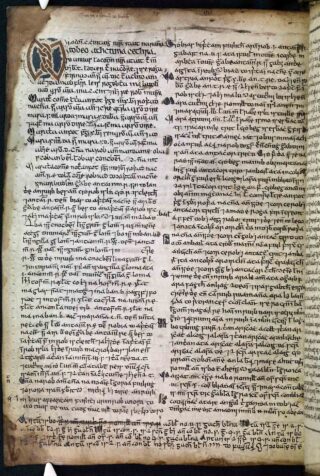

The Book of Donal O’Davoren is one of the most eminent works produced by an Irish law school, compiled in the Irish language by scribes for Donal O’Davoren over seven years in the mid-sixteenth century. The largest surviving section, known as MS Egerton 88, is preserved in the British Museum. Donal O’Davoren emerged as the most learned principal of the law school at Cahermacnaghten and his book presents a thoroughly comprehensive picture of our Gaelic past. It is still considered a rich source for the study of the ancient laws of Ireland and contains copies of some important texts of early Irish law, a legal glossary and a number of old literary tales. This work offers a fantastic insight into both the aspects of legal scholarship and the laws that governed codes of behaviour, covering almost every aspect of life in Gaelic medieval Ireland.

The O’Davoren law school at Cahermacnaghten was affiliated with other schools including the MacEgan law school at Park, near Tuam, Co. Galway, where much of O’Davoren’s book was written. Ensuring a cohesive network of thriving scholarly communities among the Gaelic kindreds was fundamental to sharing knowledge and ideas and maintaining interactions among peers. Donal and his scribes also visited the O’Doran law school at Ballyorley, Co. Wexford and the school of history of the O’Mulconrys at Ardkyle, Co. Clare.

By the late sixteenth century two legal systems were operating simultaneously in Ireland. Brehon law continued to be practised alongside English law, introduced with the establishment of an English-style provincial presidency in Connacht and Thomond in 1569. This would have shaped the society in which the law students of Cahermacnaghten would be expected to work as legal professionals. As a result, these circumstances tested the student’s flexibility and adaptability, preparing them to skilfully operate within more than one legal system.

Despite these challenges, many legal families like the O’Davorens managed to survive the initial wave of Tudor expansion through negotiation and adaptation, before falling into obscurity under the early Stuart monarchy in the seventeenth century. The schoolhouse at Cahermacnaghten was refurbished as a residence shortly after, before being eventually abandoned later in the following century. But the remains today act as a constant reminder of that great age of the Gaelic arts and leave behind a legacy of scholarly learning.

Church Island: A Poetic Family Tradition

Associated Site: Church Island, Lough Gill, Co. Sligo

Preeminent among all the professional learned kindreds were the poets, the most prolific literary group in medieval Gaelic Ireland. The poets were much more than simply composers of verse; they were well-rounded scholars and served, among other things, as historians, public officials, advisors to their chiefs, genealogists and recorders of tributes. Poets studied and trained in bardic schools until the seventeenth century, their education lasting on average seven to twelve years and demanding considerable study and sacrifice.

Although professional praise poetry was composed and publicly recited to a patron in return for a substantial payment, poetry had other important functions. In a society where power and land ownership were determined by lineage and status, poetry was a powerful tool to an ambitious lord. It was crafted to confirm a lord’s noble lineage and to legitimise his historical right to rule, therefore the patronage of poetic families was an essential requirement of a lord with political ambitions. It expressed his assertion of authority, his claims to land and affirmed his links to the territorial rule of his family and their customary right to levy tribute.

The O’Cuirnins were a celebrated family of great repute, belonging to a professional literary kindred who had practised the arts of history and poetry throughout the late medieval period. For three centuries, generations of O’Cuirnins served as hereditary poets and historians to the O’Rourke chiefs of West Bréifne at Church Island on Sligo’s Lough Gill, one of many important educational institutions in Gaelic Ireland. Here the head of the family resided and where they sustained an important school of learning, preserving their art of poetry and history for centuries.

The sylvan splendour of Church Island was the perfect location for a bardic school – an idyllic sanctuary from the outside world where the students could study and learn the art of poetry in splendid isolation. The school was located within the confines of a small medieval church, which once formed part of an abbey said to have been founded in the sixth century by Lommán of Trim.

Students attended during the winter months, typically from November to March, and studied the formation of various types of poems, metre and rhyme, as well as the diverse aspects of composition and writing in both Irish and Latin. They learned to memorise an extensive number of extraordinarily long verse poems and prose tales. Other subjects taught at the school would have included history, sagas, genealogy and traditional lore. By virtue of such extensive training and knowledge, fully trained poets held a prestigious official position in Irish society, wielding almost priestly powers. Poets earned their keep by serving the ruling dynasties. They guided their lords to glory or defeat and their verses were even believed to have the power to curse and kill. As a consequence of their profession and the high status it brought, the most favoured poets were usually given a generous pension and possessed extensive lands, which they held free of tax or tribute.

Addressed almost exclusively to their patrons, prominent aristocrats and ecclesiastical figures, the O’Cuirnin poets would have been well paid to compose lengthy elegies and praise poems that recorded, glorified and immortalised the heroic exploits of the O’Rourkes, while cursing those who crossed them. The poets’ other duties included serving as their patron’s advisors, and they would have been regularly called on to resolve legal arguments, counselling their patrons on various issues. Among several generations of O’Cuirnin poets, the more distinguished included Cormac O’Cuirnin, chief historian to O’Rourke, who in the fifteenth century wrote an account of the Battle of Moytura, now preserved in Trinity College Dublin.

However, the O’Cuirnins of Church Island were caught up in the borderland conflict between the O’Conor Sligo lordship of Carbury and the O’Rourke lordship of West Bréifne. They were eventually exposed to attack when a fire destroyed the school and its extensive library on Church Island in 1416, two years after the sacking of Sligo Abbey. Included in the many precious artefacts burned was the Leabhar Gearr of the O’Cuirnins, representing an irreparable loss of important Gaelic literature.

Many poets retained their privileged status down to the end of the sixteenth century. However, declining Gaelic power caused the collapse of the system of lay patronage that had once supported the learned families and by the mid-seventeenth century the majority of organised bardic schools had ceased to function in Ireland. Yet these schools enjoyed an enduring legacy – their very presence kept the bardic tradition alive into the following centuries, with its influence seen even in the literary revival of the late nineteenth century and, to a certain extent, in modern Irish verse and musicianship. Today, the corpus of bardic poetry that survives consists of an immense collection of some two thousand poems. This poetry is fundamental to understanding the Gaelic scholarship and culture of the past and reflects the many diverse strands of medieval Gaelic learning.