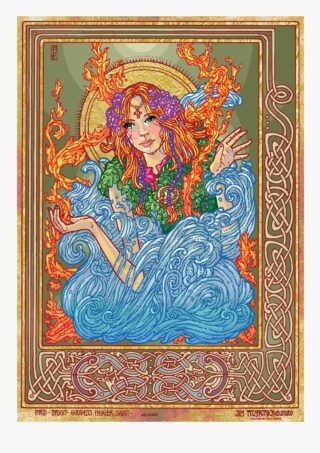

As the pre-Christian representation, the Goddess version of Brigit is the precursor to the Saint. Brigit was known as a triple goddess, connected with healing, smith-craft and poetry, and was known as the ‘Exalted One’. She was also one of three daughters of the Dagda, a god of the Tuatha Dé Danann – a powerful and magical people, who are later referred to as the Sídhe (faeries) when they retreat underground. Despite being a well-known figure today, especially through festivals held in Dublin and Louth, there is very little noted of Brigit within our mythology. Brigit is really only mentioned, briefly, during the story of the Second Battle of Moytura when she mourns the death of her son, Ruadán.

“And then Brigit came and keened her son with shrieking and with crying”

"Gods and Fighting Men" - Lady Augusta Gregory

This moment is significant as the first keening in Ireland. It could be argued that the Goddess was a predecessor to the Banshee, who is known to keen or wail when death is near.

Brigit, the Saint, much like the Goddess, is often associated with three things: fertility, abundance and protection. She was born in the middle of the 5th century; she lived, as a child, with a druid, and drank the milk of Otherworld cows – even within the Christianised version of Brigit there are elements of mythology weaved through her story. Fire became a symbol associated with Brigit after a bishop came across her praying in a small church she had founded, with a fire appearing and growing around her and the building. Legend has it that twenty nuns (Brigit being one) would guard the fire that had continued to burn for 500 years, even after Brigit’s death. The Goddess’ connection to fire may seem more tenuous than that of the Saint, however the Goddess Brigit is said to represent fire’s transformative properties through her power of healing.

There are a number of symbols that evoke the memory of Saint Brigit, beyond that of fire, including the cross of rushes, and a cloak. It is said that Brigit fashioned a cross from rushes that were on the floor so that she could convert a man to Christianity on his deathbed.

As for the cloak, Brigit used this as a means of getting what she was promised by a King of Leinster. Brigit had founded a religious house in Kildare, and as her community grew she requested land from the king in order to build a monastery. He agreed, only to renege soon after. Frustrated at his constant stalling, Brigit finally asked him to at least let her have as much land as her cloak would cover. Laughing at the meagre size of her cloak, the king conceded. Four nuns then picked up the corners and proceeded to run the four directions of the compass, continuing to cover the land until the king begged Brigit to stop, and gave her what was promised.

Today, there are many sites across Ireland that bear Saint Brigit’s name and evoke the stories that she is remembered for on February 1st. Two of these sites come under OPW care: Tully Church at the foot of the Dublin Mountains has Brigit as its Patron Saint; while Clare Island Abbey, off the coast of Mayo, is also officially known as St. Brigit’s Abbey. Meanwhile, Imbolc is affiliated with the Goddess Brigit, and is known as a cross-quarter day in which the sunlight reflects into the passage chambers of Cairn L at Loughcrew and the Mound of Hostages at the Hill of Tara.

The original Pagan tales act as the core on which to build the story of the later Christian figures; the supernatural elements of the Patron Saint’s life hark back to her mythological doppelganger. Their associations with fire, their raising by druids, their remembrance on the same day all ties these two women together, despite their veneration by people of different beliefs. The blending of one’s story with the other led to the Goddess entering the shadows to pave the way for the Saint. Now the Saint and her stories are more widely known and celebrated than that of the Goddess – certainly within Irish myth. Yet, without the Goddess would the Saint exist?

Sources:

Brennan, Martin. The Stones of Time: Calendars, Sundials, and Stone Chambers of Ancient Ireland, 1994.

Britannica.com

Gregory, Augusta. Gods and Fighting Men, 1904.

Heaney, Marie. Over Nine Waves: A Book of Irish Legends, 1995.

Mackillop, James. A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, 2004.

MacLeod, Sharon Paice. Celtic Myth and Religion: a study of traditional belief, with newly translated prayers, poems, and songs, 2012.

maps.arcgis.com – Historic Environment Viewer

Massey, Eithne. The Turning of the Year: Lore and Legends of the Irish Seasons, 2021.