Coats of arms have ancient origins, going back to the need for fighters on the battlefield to identify each other, and the ‘coat’ was initially just a coloured cloak worn over armour. The Normans were the first to develop a formal code of heraldry and by the 12th century, when St Audoen’s Church was built, many Norman lords had their own distinctive coat of arms. Gradually, heraldry became more of a status symbol for the nobility than a martial necessity, and the heraldic devices came to denote social rank and particular family traits or achievements. In the reign of King Henry V (1413-22) the use of heraldic arms without royal permission was outlawed, and in the 16th century the role of ‘Ulster King of Arms’ was established to regulate the design and granting of arms in Ireland, now succeeded within the Republic of Ireland by the office of Chief Herald of Ireland.

Each component of the coat of arms has a specific name and significance; the terms ‘dexter’ and ‘sinister’ refer to the right and left sides of the arms, but as seen from the point of view of the person holding the shield rather than of the observer. Over time, the central shield of a family’s arms was often divided into halves or quarters to incorporate the arms of a notable maternal family line. The inclusion and the style of a helmet above the shield also had a symbolic interpretation, as did each of the colours used in the design. A motto representing the values or qualities of the family was sometimes added on a banner beneath the shield, usually in Latin, French or Gaelic.

Those arms granted to English and Anglo-Irish lords could officially only be passed on to the eldest male heir. The transfer of these arms was a highly ritualised affair carried out by the Ulster King of Arms during the funeral of the deceased. The National Library of Ireland holds a collection of bound volumes from the ‘Ulster’s Office’ which detail these proceedings all the way back to the 16th century. These volumes were intended simply to keep a heraldic record of who was legally permitted to use arms, but they have become an invaluable source for genealogical research, not least in relation to the many elaborate funerals held at St Audoen’s Church in the 16th and 17th centuries.

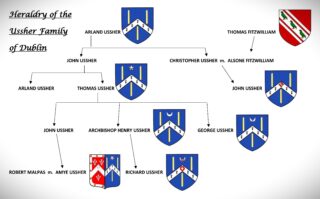

While waiting to inherit a coat of arms, the designated heir was allowed to use the arms with the addition of a stripe (or ‘label’) across the top. Younger sons, who were unlikely to inherit, often used a version with additional symbols representing their place in the family pecking order. For example, a crescent represented the second son, a star the third son, a bird the fourth son and a ring the fifth son. A diamond-shaped ‘lozenge’ coat of arms generally represented the unmarried daughter of a family patriarch. The Ussher family – one of medieval Dublin’s leading families – provides a good example of the evolution of variant coats of arms through the generations. Whilst only one living person was allowed to use a coat of arms of English origin, by contrast coats of arms for Gaelic Irish clans were granted collectively, meaning that any family member could use them.

So, what can St Audoen’s Church tell us about the use of heraldry in Ireland during this period?

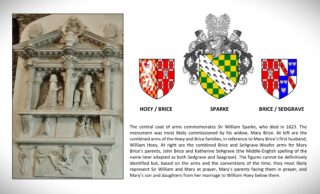

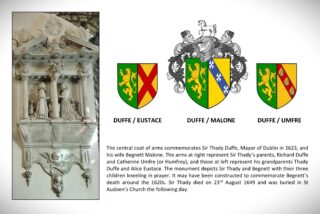

Although parts of the site have fallen into ruin at various stages of its eight-century history, the highly ornate Stuart-era memorials to the Sparke-Brice and Duffe families are wonderfully preserved in spite of their delicate plaster construction. In monuments overflowing with symbolic emblems it is the coats of arms which are placed at the pinnacle of each, representing the pride these parishioners felt about their lineage. And while any pigments and inscriptions have long-since faded away, these carefully sculpted arms help us to confirm who the memorials were built in memory of.

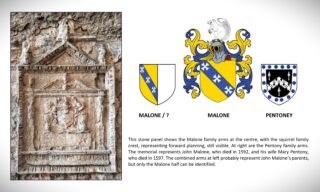

Memorials of a very similar design to the above were erected within St Audoen’s Church in memory of the families of Alderman Edmond Malone and Mayor Nicholas Weston, but exposure to the elements has left almost no surviving trace. An earlier generation of the Malones were memorialised in a smaller, though still highly intricate, wall panel which, due to its construction from stone, has lasted somewhat longer.

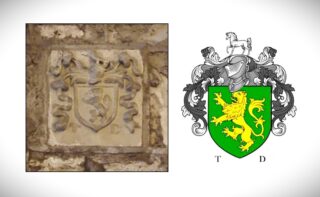

Another stone panel from this era on display inside the visitor centre is linked to Mayor Christopher SeÞgrave, who died in 1589, but it has not fared so well. The oldest identifiable coat of arms in the church is the simple stone tablet in a window recess next the the altar, still used for worship. It depicts the Duffe family arms with the letters ‘T D’.

This is believed to memorialise Thady Duffe, who was Mayor of Dublin in 1548. His name derives from an ancestor, Tadhg Dubh O’Farrell, from present-day County Longford, and in fact the Duffe and O’Farrell arms are identical.

Less grandiose were the ‘ledger’ tombstones which were set into the floor of the church. Fragments of up to 100 of these ledger stones can still be found around the site, but due to the wear and tear of centuries of footsteps only 23 remain even partially legible. Nevertheless, a handful of these retain distinct coats of arms at the centre of their design.

Although styles changed and heraldry in tombstones became less fashionable, some examples of coats of arms survive from the early 18th century. A rare bronze wall plaque commemorates Sir John Peyton and his wife Lady Rebecca Peyton, who died in 1720 and 1730, respectively. Here, the use of Peyton’s arms acknowledges his knighthood in recognition for his services as military Governor of Ross Castle.

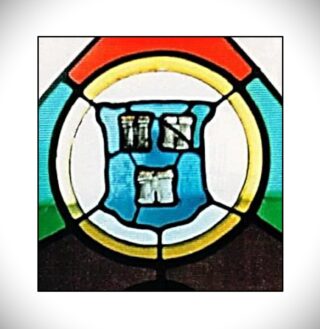

Probably the most famous coat of arms in Dublin to this day is the three castle gates with flaming beacons against a blue shield – the official arms of the city. This has been a symbol of Dublin since the 13th century, but the design was given official status in 1607 by Daniel Molyneux, Ulster King of Arms, who is buried in the vaults of St Audoen’s Church. The arms form the centre-piece of the church’s stained-glass window in reference to the innumerable Mayors and Lord Mayors of Dublin who worshipped in St Audoen’s and found their final resting place in its vaults.

By the middle of the 18th century St Audoen’s Church was no longer associated with Dublin’s high society, and that social tier was itself to become largely irrelevant following the Act of Union. However, the decline in its fortunes most likely saved it from being demolished and rebuilt to modern specifications by some wealthy benefactor, and thus we now find inside its walls a trove of architectural gems stretching all the way back to the late 12th century.

The good news is that it is open to the public, free of charge, each year (currently March to November, 7 days a week). Visitors will find all of the above information and more at the visitor centre reading desk; but for the full immersive experience ask the guides for a guided tour of the site – also free of charge!