In more recent times the name Samhain has been replaced by the now familiar term Hallowe’en. Hallowe’en has become the great festival of the macabre, a time for horror and scares, an amalgamation of ancient and modern customs. Although a number of these customs have their origins in pagan traditions, now lost in the mists of time, the actual word Hallowe’en itself has a very different background as its roots lie in Christianity. In the early church the 13th May was a feast day designated for the remembrance of all martyrs, those known and unknown. Later this evolved to be a day to honour the memory of all saints and in particular saints that did not have a separate feast day of their own. Evidence for a change of date from the 13th May to the 1st November for this feast occurs during the reign of Pope Gregory III (731 – 741 A.D.) and in 837 A.D. Pope Gregory IV orders its general observance throughout the Church. So how does “All Saints’ Day” transform into the familiar word Hallowe’en? Hallow is an old word for a saint or a holy person, its origins lying in Old English, so All Saints Day was formerly called All Hallows Day, it occurs on the 1st November so the close of the day before, October 31st, is All Hallows Eve (or Evening) and abbreviated we then have Hallowe’en. All Saints’ Day is then followed on November 2nd by All Souls’ Day a day dedicated to remembering the faithful departed and so these two days have led, for many, to this time of year becoming the primary focus for commemorating the dead.

Of course commemorating the dead is nothing new and has been a preoccupation of humanity since time immemorial. Many of the wonders of the ancient world were built precisely for this purpose. The range in size and complexity of the structures built through the centuries to house the dead or dedicated to the memory of those who have passed is simply mind-boggling. On the one hand we have the pyramids, massive passage tombs or elaborate necropoli while on the other hand we have simple stone-lined cist burials or a standing stone to mark a burial spot. Scattered within the boundaries of many of our National Monuments are memorials to our dead and these take many forms, in shape, size and material used. Depending on the time period, affluence or beliefs of those interred these objects range from simple stone or wood markers to massive, monumental mausoleums. The ones we are probably most familiar with are the standard, stone tombstones that stand silent and stoic in the grounds and graveyards of our ruined churches, abbeys, priories and friaries. The decoration on these memorials can be quite plain consisting of a simple inscription, a name and maybe a date, however many are covered in carvings and decoration, all of it symbolic in some fashion and designed to deliver a message to those who view it.

Particularly striking are the tombstones that are decorated with the Arma Christi, the “Weapons of Christ”, a collection of the symbols of the Passion. As a grouping of symbols their use dates back to at least the 9th century however it is during the 15th to 17th centuries, in Ireland at least, that they appear quite commonly on tombstones and a host of symbols can often be found carved on a single stone. Among the symbols commonly seen are a mix of the following: a crown of thorns, a ladder, the column Jesus was bound to when scourged and the ropes used to bind him to it, the scourges or whips, the hammer and nails, the pincers used to remove the nails after the crucifixion, the seamless robes Jesus wore and the dice the soldiers used to gamble for the robes, the spear that pierced his side, the rod with vinegar soaked sponge affixed, thirty pieces of silver, a bell, the rooster that crowed three times, a jar or jug, a lantern, the sword used by Peter to cut off the ear of the High Priest’s servant (and sometimes the ear itself is shown!). The sun and moon are often shown along with the Arma Christi and may represent the eclipse that took place on Good Friday or otherwise may be a simple, yet subtle, reminder of the passage of time.

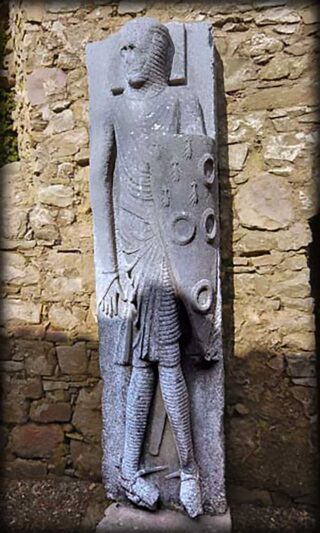

Perhaps the most eye-catching of the medieval tombs that have survived to this day are the effigial tombs; there is something striking about seeing a depiction of a figure, lying in restful repose, dressed as they would have been hundreds of years ago. As to whether the representation is accurate or not is another thing, artistic licence is nothing new! Knights, ladies, ecclesiastical figures, wealthy citizens and merchants make up the majority of those depicted in this fashion, the commissioning of these elaborate memorials requiring a certain level of affluence. The appearance of effigial tombs in Ireland begins following the arrival of the Normans in the late 12th century, with the earliest surviving examples in the country dating to the late 12th and early 13th century. What is probably the oldest tombstone in Ireland with an inscribed date, the inscription records the year as being 1253, now stands within the 19th century chancel of St. Mary’s Church in Gowran, County Kilkenny. It depicts an ecclesiastic figure named Radoulfus, shown in his priestly robes, who died on March 19th of that year.

Normally a wealth of further carvings decorated the surrounds of these effigies and it is worth keeping in mind that traces of paint have been found on these memorials; originally they were quite colourful unlike the bare stone we are familiar with today. The effigy itself can be situated on a stone box, forming a box or chest tomb, the side panels of which tend to feature images of various saints and other figures, the Arma Christi or heraldic decoration and coats of arms. The figures shown on these side panels are, erroneously, generally referred to as “Weepers”, actual weepers were usually anonymous figures posed in mourning and praying for the soul of the deceased. In Ireland many of these “Weepers” are actually saints, and those sculpted are often depicted with a feature or attribute that allows them to be identified. John for example, the youngest of the apostles is usually depicted without a beard, unlike the other apostles who are shown with an abundance of facial hair, whereas James the Greater usually has one, or all, of the following; a pilgrim staff, pilgrim bag or scallop shell. The scallop shell being familiar today from the Camino to Santiago de Compostela where the apostle himself is reputed to be buried. Fittingly, as we approach Hallowe’en, many of the figures represented on these side panels are depicted with the instrument of their martyrdom and many of them met rather gruesome ends. St. Catherine of Alexandria suffered many trials and tribulations before being sentenced to death, through the use of a spiked breaking wheel, before she was eventually beheaded. She is easily recognised on tomb surrounds as she carries or stands beside the spiked breaking wheel. In fireworks the Catherine Wheel takes both its name and form from this legend. Tradition has it that St. Simon was martyred by being sawn in half and so we see him depicted holding a massive saw. St. Bartholomew is said to have been skinned alive, before being beheaded, and is usually depicted with a flaying or fleshing knife in one hand while holding a sheet of his own skin in his other hand.

There have been certain times in history when death and mortality have become preoccupations for populations and subsequently these themes become an integral element of the psyche of succeeding generations. In particular, in the aftermath of cataclysmic events, such as wars and natural disasters there is a tendency for society to focus on mortality and the transience of the ephemeral frame. Perhaps the most catastrophic event to occur in Europe during the medieval period was the “Great Plague” or “Black Death” that struck in the mid to late 1340’s. During this outbreak it is reckoned that somewhere between one and two thirds of the population of the continent died (there is great variance in the estimates of the overall percentage of deaths but it is certain that there were massive numbers of casualties). In Ireland, the great plague struck the urban, economic centres of the country hardest, initially being brought from the continent via ship along the primary trade routes to Ireland and subsequently spreading inland, again following the commercial routes. As a result of the outbreak spreading in this fashion the areas worst affected were those where the Norman families had greatest control. John Clyn, a Kilkenny Franciscan, gives a contemporary account of events during the time of the plague. He ends his “Annals of Ireland” with the following poignant wish:

So that notable deeds should not perish with time, and be lost from the memory of future generations, I, seeing these many ills, and that the whole world encompassed by evil, waiting among the dead for death to come, have committed to writing what I have truly heard and examined; and so that the writing does not perish with the writer, or the work fail with the workman, I leave parchment for continuing the work, in case anyone should still be alive in the future and any son of Adam can escape this pestilence and continue the work thus begun.

Friar Clyn’s chronicle may have ended with the above plea, and its mix of futility and hope, but there is one further entry in his work, written in a different hand, it says simply: “Here it seems the author died”.

Friar Clyn is still known to us today thanks to the survival of his chronicles but the majority of those that fell victim to the plague were buried in mass graves, plots of land whose locations, in general, are now lost to the vagaries of time. The plague did not play favourites and the great and mighty were as likely as anyone to fall into its grip. On the north wall of the chancel of the ruins of the Cistercian Abbey of Knockmoy, in County Galway, is a surviving example of medieval wall painting. To the right of an image of Christ, the martyrdom of St. Sebastian is portrayed, two archers firing arrows into the saint’s body. During outbreaks of plague St. Sebastian was venerated and prayed to for protection and deliverance. Above this depiction of the martyrdom are six figures, three are of kings in their prime while the other three are crowned skeletons. These kings and skeletons represent the legend of “The Three Living and The Three Dead”, a reminder that death is inevitable for all. The legend also has a moral to convey as the Three Dead confront the Three Living encouraging them to repent and live good lives as their wealth and power will have no benefit in the grave. As James Shirley (1596 – 1666) writes in his poem “Death the Leveller”:

Death lays his icy hand on Kings,

Sceptre and Crown,

Must tumble down,

And in the dust be equal made,

With the poor crooked scythe and spade.

Although death may level the field, the wealthy, however, could afford to have a memorial commissioned for posterity. A specific type of effigial tomb is said to have begun to appear in the aftermath of the Black Death and it takes a form that would fit in perfectly with our modern take on Hallowe’en being a festival of fear and a celebration of the morbid. These memorials are collectively known as cadaver tombs and to us today would appear to be the product of the fertile imagination of a horror writer. There are approximately a dozen known cadaver effigies remaining in Ireland. In the case of cadaver tombs the effigy does not depict the subject at the height of their powers and health but instead they are shown after the mortal coil has been shuffled off and decay has begun its work on the physical remains. Invariably shown with the burial shroud rolled away from the body, emaciated corpses in varying states of decay greet the viewer. As gruesome as this may seem the smaller details compound the overall effect. On the most decorative of the cadaver tombs we find a host of verminous creatures, writhing around the skeletal remains of the deceased, including include beetles, lizards, snakes and worms.

The finest cadaver tomb in Ireland is that of James Rice, now located within Christchurch Cathedral at the heart of the Viking Triangle in Waterford. James Rice was mayor of Waterford on multiple occasions and twice made the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, a perilous undertaking in the 15th century. Due to the distinct prospect of dying while making the journey he commissioned his tomb in 1482, prior to a planned pilgrimage to Santiago for the jubilee year of 1483. He founded a side chapel of the medieval Cathedral in Waterford, dedicated to Saints James and Catherine, in order to house the tomb (the current cathedral was built by John Roberts in the 1770’s following the demolition of the earlier Gothic cathedral). James Rice survived the pilgrimage and is believed to have died around 1488. The tomb itself depicts the knotted burial shroud pulled open, revealing a decomposing effigy lying recumbent, eyes staring sightlessly upwards, one emaciated hand drawing part of the shroud across the body to protect the modesty of the deceased while a frog sits undisturbed atop the lower abdomen while worms crawl through gaps in his ribs. The tomb bears an inscription mentioning both James Rice and his wife Katherina Brown along with the following memento mori:

Whoever you may be, passer-by, stop, weep and read, I am what you are going to be, and I was what you now are, I beg of you pray for me, it is our fate to pass through the gate of death

Of course cadaver tombs and other memento mori were not directly intended as a means of causing fear but rather the intention was to deliver a message, literally “remember that you will die”. They offered the viewer the opportunity to reflect on their own mortality and perhaps resolve to make changes to live a better life. Although the cadaver tombs may have been the height of artistic expression of this philosophy the use of memento mori has continued to the modern day. Down through the centuries various symbols such as hourglasses, skulls and crossbones, upside down torches, the Danse Macabre, have been used to remind the observer that time is passing. The Danse Macabre, or Dance of Death, was a particularly graphic reminder that no matter a person’s station in life all must answer the call of Death. The earliest known depiction of the Danse Macabre was a mural in Paris, completed circa 1425. Typically in the Dance of Death a line or chain, sometimes a circle, of figures are depicted dancing their way to the grave with the living and the dead alternating as they advance hand in hand. All classes, from richest to poorest, are shown and it served as a reminder that all, be they Emperor, merchant or peasant, suffer the same fate and all are made equal in the presence of Death.

All memorials, in a sense, can be classed as memento mori. Although used to commemorate the dead they are tangible indicators of what is to come. They are reminders of those gone and in many cases are the only record remaining of those mentioned. It can be humbling to stand amongst the gravestones in an ancient burial ground, read a name and realise that you are possibly the first person in decades or even centuries to speak the name of that person aloud. By taking that moment to read that name you acknowledge that although now gone the person named once lived, a fellow human, whose only record of their life may be that which is inscribed on the stone before you. The classic memento mori ends with “As I am now, so you will be”, a note of finality, an admonishment that life is transient. However, we should never forget how the saying begins, we are simply the latest in a long line of generations of humanity that stretches back to prehistory, and it reminds us that we today have something in common with those now gone, for “As you are now, so once I was”.

James Barry is a native of Co. Waterford. Currently Head Guide in Reginald’s Tower where he has been working as a guide since 2002. Growing up next door to a graveyard sparked a lifelong interest in memorials to the dead.