Her-story and Her-itage

Women's history, their stories, and their achievements, are often layered within or hidden behind the stories and accolades of men.

We are finally entering a period where women's stories are highlighted and celebrated, and the below names are just a few of the remarkable women associated with our historic heritage sites.

This is Herstory

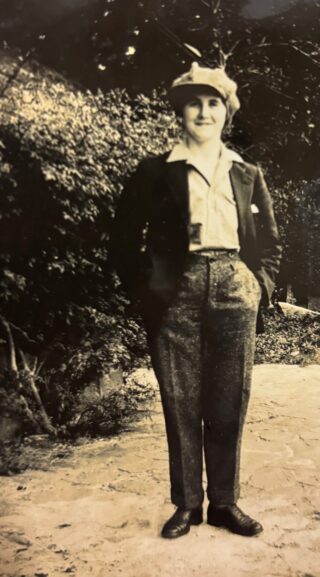

Margaret O’Sullivan – Garinish Island

*1908 – 1999*

Margaret “Maggie” O’Sullivan lived most of her life on Garinish Island. She began working for the Bryce family in 1926 when she was still a teenager, acting as the housekeeper, attending to high-profile guests to the island, including most of the Irish Presidents who were serving during her lifetime.

Margaret was a fiercely independent woman, rowing her boat back and forth to the mainland to do her shopping and attend mass every Sunday with her dog. Margaret lived on the island until 1998, and was the last permanent resident of Garinish Island.

In 1992 she was recognised by Glengarriff Tourism & Development Association for her contribution to tourism in the area.

Nancy Wyse Power – Custom House Visitor Centre

*1889 – 1963*

Nancy Wyse Power was a member of Cumann na mBan (1915), the Gaelic League (1901), and a Civil Servant. She received her BA in Celtic Studies from UCD, and continued to do a PhD in Germany on Celtic Philology.

Nancy was heavily involved in the Nationalist cause, helping to deliver messages during the 1916 Easter Rising, and supporting the families affected by the Rising in the subsequent years. She was appointed honorary secretary of Cumann na mBan in 1917.

In 1923 she began working for the Department of Industry and Commerce, and in 1932 was personally requested to be the private secretary of Seán T. O’Kelly, within the Department of Local Government and Public Health at the Custom House.

Nancy was one of the first female Principal Officers in the Free State civil service, and used her position to advocate for equal rights for women in the civil service.

Elizabeth O’Farrell – Kilmainham Gaol Museum

Elizabeth O’Farrell’s story has been hidden from history for years. She was literally erased from key events in 1916, airbrushed from the photos as though she were never there.

It is now known and accepted that Elizabeth and Julia Grenan were in a relationship, living with each other for most of their lives, and doing almost everything together. The two joined multiple organisations including the Gaelic League, the Irish Women’s Franchise League, the Irish Women Workers’ Union, and Inghinidhe na hÉireann. They were taken under the wing of Markievicz and trained in the use of firearms.

In 1916, Elizabeth was assigned to the Irish Citizen Army, delivering messages to Athenry, Spiddal, and Galway City, before returning back to Dublin to medically attend to the injured, and deliver ammunition from the GPO to other garrisons in the city. Both she and Grenan cared for James Connolly after he was shot.

Elizabeth was picked by Patrick Pearse to discuss surrender terms with the British military, and was sent out into heavy fire, armed with only a white flag and a Red Cross symbol. It is she who stands alongside Pearse to deliver the unconditional surrender to General Lowe. Lowe assured Elizabeth that she would not be imprisoned, but after the surrender she was strip-searched and held in both Ship Street Barracks and Kilmainham Gaol. Lowe ordered her immediate release upon hearing of her imprisonment.

During the War of Independence both Elizabeth and Julia delivered dispatches to the IRA, and were strongly anti-treaty, helping to raise funds for the families of anti-treaty prisoners.

In 1967 a plaque was unveiled at Holles Street Hospital, where Elizabeth once worked as a mid-wife, and a foundation to support nurses in their postgrad studies was created. In 2012 City Quay Park, where Elizabeth was born, was renamed Elizabeth O’Farrell Park.

Both Elizabeth O’Farrell and Julia Grenan are buried beside each other in Glasnevin Cemetery.

Gwendolen Guinness, The Countess of Iveagh – Farmleigh House & Gardens

*1881 – 1966*

Lady Gwendolen Guinness was one of few women of her time to be elected as a Member of Parliament in the House of Commons. She won her seat in the Southend-On-Sea by-election in 1927, which she kept until 1935.

Though at times Gwendolen was reduced to a fashion icon rather than a parliamentarian, with one report by The Daily Telegraph in 1934 stating that people were ‘eager to see her fashionable clothes’, Gwendolen Guinness remained steadfast in her fight for and defence of women’s rights.

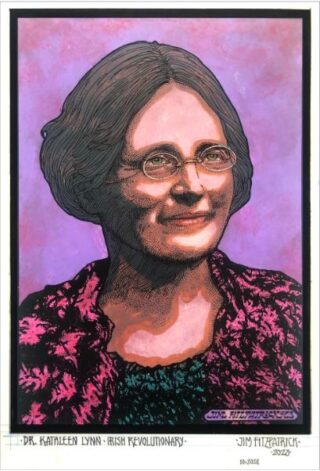

Dr. Kathleen Lynn – Kilmainham Gaol Museum

Dr. Kathleen Lynn was involved in multiple movements throughout her life, including the suffragist, labour, and nationalist movements.

She was a key player during the 1916 Easter Rising, having taught the members of Cumann na mBan first aid, and was Chief Medical Officer of the Irish Citizen Army during the rebellion. She was imprisoned for a time in Kilmainham Gaol for her part in the Rising.

However, her revolutionary involvement is just one side of Kathleen Lynn’s story. She studied in Manchester, Dusseldorf, Dublin, and the US, and was a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1909. From 1910- 1916 Lynn was the first female resident doctor in the Royal Victoria Eye & Ear Hospital.

She is remembered for her work in St. Ultan’s Hospital for infants and their mothers, and she helped further international research on TB eradication.

Hilda Grove Annesley & Sylvia Cooke Collis – Annes Grove Gardens

*1869 – 1961* – Hilda

Hilda Grove Annesley, nee Macnaghten, married Richard Grove Annesley in 1907 and together they were responsible for creating the paradise garden of Annes Grove near Castletownroche in North Cork. For over fifty years she was the constant presence at Annes Grove welcoming family, friends and visitors from far and near. She was happiest when out riding – she rode side saddle all her life and was admired as a very fine horsewoman.

In 1912, she wrote to Dick (Richard) telling him if she should die suddenly or killed out hunting that he was not to grieve too much as “we must all die someday and I have no wish to live to be older than 50”. She did in fact live until 1961 at the age of 92. Through her diaries and memoirs Hilda left behind an account of country living from the first half of the 20th century.

*1900 – 1973* – Sylvia

Daughter of Hilda Grove Annesley from her first marriage to Henry Cecil Phillips, Sylvia Cooke Collis was born in Glanmire, Co Cork but spent most of her youth in Annes Grove after her mother married Richard. Like her mother she loved the outdoor life and was involved with horses, dogs and fishing (her step father was a very keen fisherman). She also developed an interest in art and studied under John Power at the Crawford Municipal School of Art and later trained with Mainie Jellett, with whom she became friends.

She was good friends with another famous neighbour in North Cork, Elizabeth Bowen, who encouraged Sylvia further in her endeavours. Sylvia exhibited widely in the mid-twentieth century and was known as a modern artist, influenced by Jellett herself and the Fauve movement. No longer a household name, her art nevertheless has stood the test of time and may be due a revival.

- courtesy of Aileen Spitere

Countess Constance Markievicz – Kilmainham Gaol Museum

*1868 – 1927*

Constance Markievicz was heavily involved in the revolutionary fight for Irish freedom and in Irish politics. Her involvement in the republican movement dates to 1908, when she joined both Sinn Féin and Inghinidhe na hÉireann – both of which she became an executive member of in 1911.

Markievicz was sympathetic to the workers cause during the Lock-out in 1913, and set-up soup kitchens. She was the honorary treasurer of the Irish Citizen Army, and was responsible for the merging of Inghinidhe na hÉireann with Cumann na mBan.

During the 1916 Easter Rising, Markievicz was second-in-command to Michael Mallin at Stephen’s Green/Royal College of Surgeons, a role for which she was imprisoned for 14 months. She was held in Kilmainham Gaol for a short period, before being transferred to Aylesbury Prison.

Markievicz was the very first woman elected to Westminster in 1918, but as a member of Sinn Féin, and someone who did not recognise the British Parliament, she refused to take her seat. In March 1919 she became minister for labour in the first Dáil Éireann.

Constance Markievicz is now buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

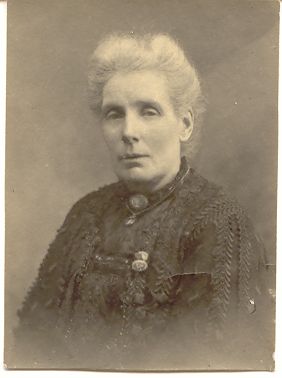

Margaret Pearse – Pearse Museum, St Enda’s Park

*1857 – 1932*

Margaret Pearse was a staunch nationalist and elected member of Dáil Éireann in 1921; vocally Anti-Treaty, Margaret was dedicated to keeping the memory of her two sons (Willie and Patrick Pearse) alive in everything that she did after the executions in 1916.

Margaret raised funds to keep the school Patrick set-up, St. Enda’s, running for as long as possible, travelling to America in 1924, raising $10,000 while there.

Margaret Pearse was given a state funeral upon her death, and is now buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

Lady Anne Wandesforde, The Countess of Ormond – Kilkenny Castle

*1754 – 1830*

Lady Anne, born Susan Frances Elizabeth (Anne) Wandesford, was heiress to the family mines in Castlecomer.

She married into the Butler family, and focused on healthcare within the Castlecomer area, organising the set-up of a fever hospital and infirmary during the 19th century.

Lady Louisa Conolly – Castletown House & Parklands

*1743 – 1821*

Lady Louisa dedicated the later years of her life, after her husband’s death in 1803, to charitable works.

She established a female charter school, as well as industrial schools were children could be trained in various trades. She also had a church built, and believed that both Catholics and Protestants should be educated together.

Angelica Kauffman – Rathfarnham Castle & Dublin Castle

*1741 – 1807*

Renowned neoclassical-style painter Angelica Kauffman is famous for her portraits and history paintings, capturing some of the most influential people of her time through her art.

A founding member of the Royal Academy in London, Kauffman’s talents were highly sought after by the elite, including the Earl of Ely of Rathfarnham Castle. She visited Ireland briefly in 1771, and some of her portraits of the Loftus family still reside in the Castle, including one of the Earl himself, Henry Loftus (see below).

Some of her historical paintings can also be viewed within the State Apartments of Dublin Castle.

Grace O’Malley, The Pirate Queen – Clare Island & Kildavnet Castle

*1530 – 1603*

The legendary Pirate Queen, Grace O’Malley, was a formidable woman, asserting her leadership in a man’s world.

From a young age Grace showed determination, cutting her hair short to look like a boy so that she could board her father’s ship, when he refused her access. This action earned her the nickname of ‘Gráinne Mhaol – Grace the Bald’.

Her first husband, Domhnall O’Flaherty, engaged in ongoing fighting against the Joyce’s for control of Hen’s Castle in Co. Galway. After he was ambushed and killed by his enemies in 1565, Grace defended the castle, refusing to surrender to her enemies, and forcing them to retreat.

Grace became known as one of the most feared sea captains in Ireland, commanding a fleet of ships and an army of 200 men.

Sir Nicholas Malby, Governor of Connaught, said of her at the time that she ‘thinketh herself to be no small lady’ – she was not one to hide her light under a bushel.

Sir Henry Sidney proclaimed Grace ‘a notorious woman in all the coasts of Ireland’.

Today, many OPW sites are associated with Grace O’Malley, including Kildavnet Castle which bears her name ‘Granuaile’s Tower’, and Clare Island where she is said to be buried.

Portrait Miniatures and the Irish Country House

A catalogue of the collection of portrait miniatures donated by Edmund Corrigan to the Irish Georgian Society (IGS) for display at Castletown and Doneraile Court has been published by the IGS in October, 2024. It provides comprehensive catalogue descriptions on the sitters in the portraits and the houses they resided at. Author Kevin Mulligan has unearthed vast quantities of information that connects miniature to miniature, family to family, house to house adding significantly to our understanding of the interlocking family and social histories of Irish country

houses. Paul Caffrey, leading expert on miniatures notes ‘few historic family collections of miniatures survived in Ireland making this a truly remarkable collection of national importance’.

In addition to the detailed catalogue entries and images of sitters there are carefully sourced illustrations of the houses the sitters lived in. The watercolours, pen and ink drawings and paintings of the houses, topographical views and landscapes work especially

well. Kevin weaves a magically interwoven account throughout the 221 catalogue entries.

William Laffan contributes a fascinating essay on the history of portrait miniatures which sets the context to the significance of Edmund’s collection and the links to literature are particularly

effective.

The background to the making and researching of the catalogue goes back to 2016 when miniatures of the Boyle and Fitzgerald families were presented on loan to Castletown and went on

display in the Print Room. The following summer Donough Cahill, Director of the Irish Georgian Society (IGS) raised the possibility of a substantial miniature collection being made available for Castletown on long-term permanent loan. The Collection was to be donated to the IGS by Edmund Corrigan. Following agreement with the Director of National Historic Properties, Rosemary Collier, Dorothea Depner and I progressed plans for the Edmund Corrigan Collection of portrait miniatures, in association with the

Castletown Foundation, to be housed at Castletown. By the middle of 2018 the IGS was getting ready to transfer the miniatures and it was agreed that a small selection of the miniatures would be housed at Doneraile Court – Edmund had fundraised for the earlier conservation works at Doneraile Court

in the 1980’s and wanted to support OPW’s work now in presenting suitable and interesting collections at Doneraile. Ludovica Neglie made the first inventory of the collection investigating provenance with Edmund.

The Chairman of the Castletown Foundation (CF) David Sheehan together with the late Jeanne Meldon, Director and former Deputy Chair of the CF commenced work on how best to display

the miniature collection. Pat Murray, another Director of the CF, had been supporting Edmund in his collecting and together plans started to come together. David knew that Edmund was clear the

style of presentation was to be Country House and David Sheehan designed a scheme for the Lady Kildare Room. Conservation of the Lady Kildare Room and bringing it into visitor tours had been

under discussion for some time. The arrival of Edmund’s collection and the challenge of how best to display it was the catalyst to the conservation project. Jeanne had a wonderful knowledge of the families and the houses and gave much time and effort into organising the groups by family and houses. David

Hartley at Castletown took control of the care of the miniatures working to David’s layouts for the room and Sandra Murphy took charge of ensuring the guiding team prepared for interpreting

the collection to visitors. Joanne Bannon, Historic Collections Registrar, led on the loan agreement documentation between OPW and the IGS in line with the Museum Standards Programme of Ireland (MSPI). The cases for display of the miniatures were at the house including the Luggala bookcase from the Green Drawing Room, upcycled unused frames and furniture from the Farmyard. It all combined to make a most suitable receptacle for the collection. A beautiful porcelain desk set donated by the late

Della Howard through the London Chapter of the IGS is part of the displays in the Lady Kildare Room and it was the late John Redmill and John Berger who presented that to Castletown. In parallel work was beginning to take off on the upgrade and conservation of the Ground Floor at Doneraile Court.

It was so special that Edmund could be present when Doneraile Court – a house he had fundraised for and donated several paintings to – re-opened in June 2019. He could see the interiors come back to life with two stunning framed displays of his portrait miniatures. It was another day of great celebration when in the final few days – unknowns to us - pre Covid lockdown – we gathered on 6 March, 2020 to view the collection installed in the Lady Kildare’s Room together with the celebration to mark the

acquisition of the Duchess of Leinster portrait by Reynolds – a joint purchase by the OPW/CF and the Friends of the National Collections of Ireland (FNCI). It was a delight to see Edmund enjoy seeing the miniatures presented so magnificently. When the second phase of Doneraile Court was completed we were delighted that Edmund was able to view the displays in May 2023, just months before his untimely death. The two interiors of Castletown and Doneraile fittingly bookend the Foreword to

the newly published catalogue on the Edmund Corrigan Collection. A job well done and a fitting testimony to excellent outcomes for Ireland’s cultural heritage from the careful nurturing of private philanthropy with charitable and public institutions. The Edmund Corrigan Collection at Castletown and

Doneraile Court is something we can all be proud of.

From the Blasket Islands to Springfield Massachusetts A Well Worn Path

For the past twenty five years, a group of Dingle Peninsula businesses make their way to Springfield Massachusetts for the

Big E – the Eastern States Exposition – a three week event that draws 1.7 million visitors. It is a well worn path in both directions and very much a meeting of friends.

Springfield has an amazing connection with West Kerry and the Blaskets, very much evidenced by the gathering of the city’s great and good, including many Blasket descendants, at a recent exhibition opening in Springfield Museums which celebrated the

heritage and impact of the Blasket islanders in that part of the world. The temporary exhibit was the first fruit of a Memorandum of Understanding signed last May between the OPW and the Museum. The guest of honour was the remarkable Mairéad Kearney-Shea, at 102 years young, longtime Springfield

resident and the only surviving woman born on the Great Blasket.

That the OPW and the Blasket Centre in particular would be represented at such an occasion and at the Big E is a natural expression of the deep and very much current ties of history, kinship and friendship that are so important to nurture today. My visit, which followed a similar trip by then Minister Patrick O’Donovan in September 2023, allowed me to reach out and thank places such as the John Boyle O’Reilly Club, the Sons of

Erin and the Irish Cultural Centre of New England who regularly organise tours to Ireland and see the Blasket Centre as a

highpoint of their trip.

My Springfield trip coincided with that of a Kerry County Council delegation led by Cathaoirleach Breandán Fitzgerald and Irish Consul General, Sighle Fitzgerald. This significant combined representation was noted and greatly appreciated by

our Western Massachusetts friends, at all levels.

Springfield is an intrinsic part of the Blasket story. Waves of Blasket emigrants sought a place where they could deal with the enormous dislocation of leaving their native home in a place where they could at least share their language and culture and have a supportive community network. That difficult transition and their subsequent success in their new country is the foundation of a shared and invaluable heritage that is enormously

important – on both sides – now and into the future.

The Oldest Grave at the Rock of Cashel

Despite the Rock of Cashel being a singularly unique collection of medieval buildings perched dramatically on a natural limestone outcrop, questions from visitors often concern not the buildings, but the graveyard. While people are always intrigued to hear

that the Rock of Cashel is still an active burial ground, one of the most common questions we receive is ‘which is the oldest grave?’ The answer to this question is not as simple as it might seem. While graves from the eighteenth and nineteenth century

can be seen dotted throughout the graveyard, older graves can be found inside Cormac’s Chapel and St. Patrick’s Cathedral, although most are not in their original location.

Within Cormac’s Chapel sits a large sarcophagus of early-twelfth century date. Thought to be the tomb of Tadhg Mac Carthaig, the brother of the chapel’s builder, Cormac Mac Carthaig, it now

sits against the west wall of the chapel.

Its original location is unknown, but it was likely placed in a recess in an earlier church on the site that no longer stands.

Elaborately carved with intertwining animals in the Urnes style, it likely dates to the mid-1120s, shortly before the construction of the chapel between 1127 and 1134. However, excavations carried out in and around Cormac’s Chapel in 1992 and 1993 revealed graves possibly as old as the sixth century which could have formed part of an early royal graveyard at the site connected to the traditional kings of Cashel, the Eóganachta. These, then, would be the oldest graves on the site. However, none of these are marked above ground level.

Several medieval grave-slabs can also be found inside St. Patrick’s Cathedral. In the early-nineteenth century Archdeacon Henry Cotton made an effort to collect the better examples of carved stone at the Rock and gather them together within the confines

of the cathedral. Many of these are illegible but the earliest identifiable slab dates to 1503 and belongs to a Julius O’Kearny, an attendant of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. This, then, would be the

earliest identifiable grave with a date attached to it. A second slab, located in a side chapel in the north transept, dates to 1506 and belongs to Patrick Connolly, Burgess of Cashel, and Joanna

Wale, his wife. Several others date to the early-sixteenth century including the grave-slab of the Archdeacon of Cashel, Robertus Hackett, who died on 10th December, 1510. However, one small fragment of a grave-slab in this area may date to the late-thirteenth or early fourteenth century. All that remains is the bottom of the slab which shows a pair of pointed shoes, and the bottom of a cloak that reaches the figures ankles. While no inscription survives, the style makes it clear that it is from this time period. Another slab, again from the late-thirteenth or

early-fourteenth century, is hidden away inside a mural passage in the nave of the cathedral, where it has been reused as a

lintel stone. Considering this portion of St. Patrick’s Cathedral dates to the late thirteenth century, the slab likely dates to this period or earlier as there is no evidence that the slab was inserted later.

In the two side-chapels of the north transept, are the remains of sixteenth century altar-tombs, again collected together by Archdeacon Cotton. In the north side-chapel, the remains of an altar-tomb depicting various saints can be seen, produced by the famed O’Tunney school of sculpture. In the south side-chapel of the north transept are the very well-preserved remains of a second altar-tomb, again depicting saints, this time produced by the Thurles school of sculpture. While much of these tombs have now been lost, they likely had a full effigy on top. These may not

be the earliest tomb sculptures to have survived on site, but they are certainly some of the finest.

With graves dating back possibly as far as the sixth century, and the earliest identifiable grave-slab dating to 1503, the graveyard continues to intrigue visitors. The questions we receive show a desire from visitors for a human connection to the site, one that goes beyond history and architecture, and one that connects people to those for whom the Rock of Cashel was part of

everyday life.