Perhaps one of the greatest artistic achievements of the early Middle Ages in Ireland is the high cross. Capturing our imaginations for centuries, these spectacular stone monuments have long remained as iconic cultural landmarks on the Irish landscape. A product of the Irish monastic community, these symbols of Christianity first appeared on our landscape from around the ninth century when monastic learning was in its heyday, and continued to be carved into the twelfth century, when the coming of the Anglo-Normans marked the beginning of the end of the high cross tradition. The cross’s designation “high”, first used in the Annals over a thousand years ago, seems to be fitting, as the gracefully proportioned monuments can reach up to a height of six metres. Unlike the modern incarnations today, the original high crosses were never intended to mark places of burial. Instead, they were used as boundary markers of significant territories or sacred land and as monuments to political power. Though they may have served a wide variety of functions, their main purpose was predominantly religious. The cross’s intricately carved compositions of Old and New Testament scenes were used to teach the Bible’s message and to encourage piety, devoutness, prayer and reflection, fulfilling a similar role of the frescoes on continental churches. This educational focus was manifested in some of the most outstanding works of religious stone carving in both an Irish and European context, and was central in continuing the tradition of monumental stone sculpture into the twelfth century.

By the seventh and eighth centuries, the great centres of Christianity at Armagh, Clonmacnoise, Kildare and Glendalough were becoming the most important religious centres in the country. The following century witnessed the gradual development of these monasteries and others like them, into small urban centres surrounded by large lay settlements. These monastic communities functioned as major players in the hierarchies of power operating in Irish society, endowed by powerful kings who regarded the monasteries as part of their royal domain. Indeed, the scale, engineering and elaboration of the larger crosses in particular, represents the wealth and authority of both the monastery and its patrons and suggest that powerful individuals of status were involved in their construction. The south cross at Monasterboice, Co. Louth records the patronage of Muireadach while High King Flann Sinna was responsible for the erection of the Cross of the Scriptures at Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly. Likewise, an inscription on the cross at Tuam, Co. Galway links its construction to a royal O’Conor patron. It was this political landscape that formed the backdrop to the establishment of the high cross tradition in Ireland, which, along with the church, formed the core of these settlements.

The monasteries were great champions of art, architecture and learning and readily encouraged the production of manuscripts, metalwork and the study of the scriptures as part of their spiritual devotion and service. The meticulous carvings of complex repertoires of biblical scenes adorned on the high crosses are a testament to the extent of the monk’s study and the great ability of the artists. Both faces of the crosses and even their narrow sides are exquisitely carved with panels illustrating biblical events, often including Adam and Eve, the Last Judgement, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection of Christ, among others, in an array of forms. In contrast to the often-stylised figural representations in early Irish art, the sculptured figures on these crosses are generally naturalistic, suggesting that their origins derive from the classical world. In terms of symbolism, the imagery of Adam and Eve can be viewed as representing the beginning of sin, the Crucifixion may signify a new beginning, while the Last Judgment symbolised the end. Collectively, these range of scenes appear to symbolise the universe as seen through the eyes of early Christian monks. The centre of the cross is often surrounded by a ring, giving the cross it’s iconic and instantly recognisable form. Though the ring had a structural purpose, it has also been suggested that this was combined with a symbolic function, possibly representing the cosmos and that the Crucifixion, depicted at the centre of most high crosses, was the most important event in the history of the cosmos, although opinions still remain divided on this.

These crosses were objects of veneration, but their educational and religious value was also recognised from the early ninth century following the Council of Paris in 825 when the strict rules discouraging the use of images in a religious context were somewhat relaxed. Louis the Pious, Emperor of the Carolingian Empire and the only surviving adult son of Charlemagne, promoted the painting of frescos to illustrate scenes from scripture such as those on the walls of his chapel at Ingelheim in what is now Germany. But the wall space and interior light needed to create such frescos generally did not exist within the small confines of early Irish churches and instead, led to the to the development of the high cross in the second half of the ninth century in an effort to convey a particular idea or message from the Bible in visual form. The value of images as a means of educating the masses cannot be over-simplified however, and it must be noted that many of the complex imagery found on Irish crosses were aimed at a knowledgeable audience, rather than the less informed lay congregations. From the more simple versions to the most richly sculpted crosses, they all demonstrate the importance placed on the illustration of church doctrine in conveying or instructing Christian ideas to the already educated monastic community and possibly, but to a lesser extent, to the largely illiterate laity. The figure-carved, scriptural crosses that contain numerous, carefully chosen selections of narrative biblical scenes must have conveyed certain messages to the viewer. Also containing images from scripture, they served a specific purpose of aiding in the teaching of scripture and preaching a variety of themes. The images provided opportunities for devotional reflection and may even echo the contemporary, popular prayers of the people.

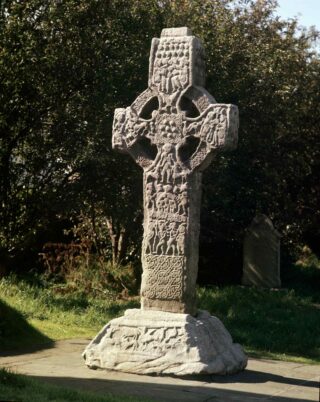

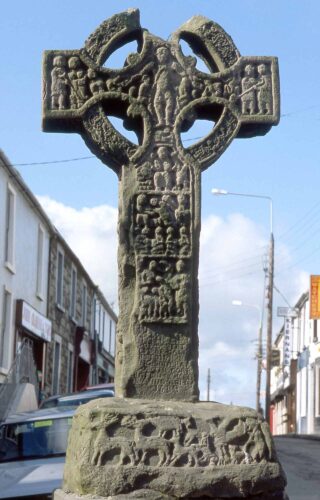

These great scripture crosses represent the pinnacle of the high cross tradition in Ireland. Perhaps the most famous and impressive of the scripture crosses are the highly sophisticated “Cross of the Scriptures” at Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly and the exquisitely preserved south cross or “Cross of Muiredach” at Monasterboice, Co. Louth. Both crosses are richly adorned with extensive scenes from Biblical events including the Passion, Death and Resurrection of Christ, the Last Judgement and the Adoration, while the Crucifixion, the central theme of most crosses bearing figure sculpture, lies at the centre of the head of both crosses and is clearly the focus of attention. This appearance of the Crucifixion on Irish crosses may reflect the growing interest in the Passion and Crucifixion in the Carolingian Empire from the ninth century. Muirdeach’s Cross at Monasterboice appears to convey the message of Christ being Lord of both heaven and earth and similarly, the Cross of the Scriptures may symbolise Christ as being the figure at the centre of the Universe. Associated with the educational function of the crosses is their use as a preaching tool. Much of the iconography on the South Cross at Kells, Co. Meath alludes to the Eucharist and has led to suggestions that Mass may have been performed in front of the cross.

Among the more standard images of the Crucifixion, Adam & Eve and Cain & Abel, the Market Cross at Kells, Co. Meath has some unusual representations of the life of the desert hermits St. Paul and St. Anthony on both the right and left arms of the cross, their occurrence which is an extremely rare survival.

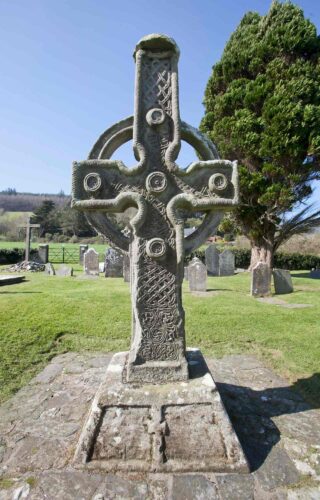

Contemporary with the great scriptural crosses are the pair of sandstone crosses at Ahenny, Co. Tipperary, but rather than being adorned with biblical scenes, both crosses are decorated with intricately carved geometric, interlace, spirals and animal designs with figure sculpture confined to their bases. The style of the ornament and certain elements that imitate metal binding strips and studs, clearly resemble those found on bronze objects of the period, suggesting that these are essentially metal work crosses translated into stone.

The ninth and tenth centuries witnessed the emergence of extraordinary stylistic developments of the high cross. They became larger and more architectural, while their shafts were divided into panels in which the iconography became more ordered and methodical. The range of scriptural crosses became more complex and this can be illustrated in the richly elaborate iconographical programme of the Tall Cross at Monasterboice, which stands to a height of over six metres and is Ireland’s tallest high cross. The detail of the figures is remarkably well preserved, which have a vivacious quality not paralleled elsewhere, depicting the Old Testament figures of Adam & Eve, David & Goliath, Moses, Samson and Elijah along with graphic scenes from the Baptism and the Crucifixion.

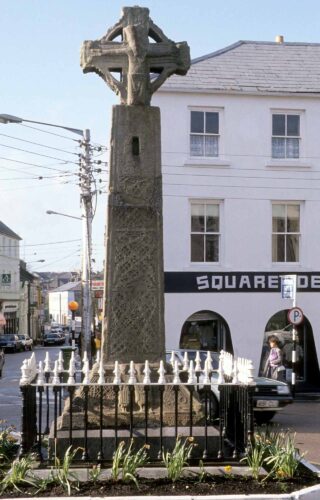

Following a scaling down of scriptural crosses during the course of the tenth century after which there was a brief hiatus, the twelfth century witnessed a major revival in cross carving, featuring new artistic expressions based on contemporary Scandinavian styles. The characteristic ringed cross head became more compact or sometimes even absent, while less emphasis was placed on scriptural content. Biblical scenes had largely given way to high relief carvings of Christ and figures of bishops or abbots. The prominence of the bishop appears to be linked to the church reforms of the period. Though the iconography of the crosses is dominated by these two figures, displayed either one above the other on the same side, or each figure on either side of the cross, other ornament is featured, notably panels of geometrical designs and interlace patterns. The shafts are usually covered in fine interlace and complicated animal patterns in which diagonally arranged beasts are entangled in coils of snakes. This can be best illustrated in the crosses at Dysert O’Dea, Co. Clare and at Tuam, Co. Galway where Christ with his outstretched arms takes centre stage on both crosses above figures of local bishops or saints.

Ireland’s contribution to early Christian art is nothing short of exceptional. The high cross tradition represents one of the greatest artistic achievements of monasticism during Ireland’s so called Golden Age of Saints and Scholars that foreshadowed the great Romanesque movement of the twelfth century. Just as the illuminated manuscripts used text to illustrate biblical messages, the high crosses used imagery to convey the great depth of knowledge of the Irish monks and to elucidate the foremost teachings of the Bible. Though much of the symbolic significance of the cross’s interlace and geometrical ornament is lost to us and many interpretations of their rich biblical imagery have proven to be controversial, it can be agreed that the creation of the crosses was a colossal undertaking and even after a thousand years, they cannot fail to impress. Furthermore, the artistic indulgence represented by such lavish monuments cannot be clarified with one simple explanation. Though the crosses may have been viewed as symbols of Christianity and instrumental in teaching the Christian message, some of the larger crosses may have been erected as a symbol of authority as much as a reflection of Christianity. The crosses at Kells, Clonmacnoise and Monasterboice represent the legacy of some of the most powerful ecclesiastics, kings and aristocracy of early medieval Ireland and reveal a cooperation between the church and these powerful individuals in the creation of Ireland’s most celebrated stone monument. Though the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in the late twelfth century heralded the beginning of the end of high cross production in Ireland, the 250 or so monuments that still survive on the Irish landscape today hold a special significance and to many, have become an emblem of Celtic identity. They act as a constant reminder of our unique artistic past and of Ireland’s outstanding contribution to art, architecture and education.