Every Halloween, people around the world dress up and take part in festivities, yet few are aware of its roots in the ancient festival of Samhain. In Irish folklore, the veil between our world and the supernatural draws thin at this time. It is a liminal phase, a turning of the year.

***************************************************************************************

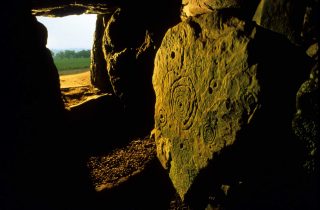

Samhain takes place roughly halfway between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice, marking a transition between the lighter half of the year and the darker half. Astonishingly, the ancient inhabitants of this island were able to plot and track the movements of the sun in the sky through the year. The Mound of the Hostages at Tara Hill is a 5,000-year-old Neolithic passage tomb. There, the rising sun illuminates the inner chamber at both Samhain and Imbolc (which coincides with Brigid’s Day – more on that in a future post). A similar phenomenon takes place in another Neolithic site in Co. Meath, the Loughcrew Megalithic Cemetery, also known as Slieve na Calliagh (Hill of the Witch). According to local folklore, the Loughcrew site was created by An Cailleach Bhéara, a powerful figure in Irish mythology. It was she who brought about winter, a necessary time to draw inwards before the rebirth of spring.

In Irish, Scottish, and Manx myth, the Cailleach is a divine hag and ancestor, associated with the creation of the landscape and with the winter. The word derives from the old Irish for ‘veiled one’.

In Irish, Scottish, and Manx myth, the Cailleach is a divine hag and ancestor, associated with the creation of the landscape and with the winter. The word derives from the old Irish for ‘veiled one’.

The story of witches in Ireland can be traced back to Viking society, which shaped Ireland from about the 11th century. Women who could ‘see the future’, known as völva, had an esteemed place in society, as evinced by the Viking burial sites and mythology. The völva practised a kind of ecstasy magic known as seid. Their visions were induced through the use of hallucinogenic herbs, particularly those of the nightshade (Solanceae) family. A rare plant nowadays, henbane (Hyoscamus niger) is mostly found around archaeological sites in Dublin. Highly toxic, it is suggested that völva may have applied the herb and relatives such as deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna) topically so that the chemicals were more safely absorbed. These two nightshades are also ingredients of the infamous ‘flying ointment’ which is reported as inducing a sensation of flying. Deadly nightshade was important herb employed by the witch healers as it inhibits uterine contractions when miscarriage threatens. The modern medication atropine was originally extracted from this plant. Atropine is used today to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. Atropine eye drops are commonly used by eye doctors to dilate the pupils.

Witch healers used Foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) as a cure for dropsy and other heart related ailments. The precise mechanisms of how it worked were mysterious to medical administrators until an English physician, William Withering, investigated its affects. His attention was drawn to the foxglove and its properties in the first place when a wise woman cured his patient of dropsy with a tea made of it. The heart drug digitalin was later extracted from foxglove. Digitalin increases the action of the heart and makes it more regular. Like many of our most important plant medicines, it has the power to save a life and also to end it – for a healthy person ingestion of foxglove can be fatal.

Elder (Sambucus nigra) has been called “the medicine chest of the country people” as it can boost immunity and act as an anti-inflammatory. Despite these positive attributes, it often has a curiously negative role in folklore. It is said that to burn it will cause the devil to appear and that if you use its wood to make a cradle it is an invitation to the fairies to steal your baby and replace it with a changeling. Perhaps these stories are a testament to its medicinal properties which were perceived as magical.

The aos sí (faeries) are said to live underground in fairy forts, across the Western sea, or in an invisible world that co-exists with the world of humans. In folk belief and practice, they are often appeased with offerings, and care is taken to avoid angering or insulting them. They are seen as fierce guardians of their abodes —whether a fairy hill, a fairy ring, a particular loch or wood, or a special tree (usually hawthorn). You would be well advised not to harm hawthorn (𝘊𝘳𝘢𝘵𝘢𝘦𝘨𝘶𝘴 𝘮𝘰𝘯𝘰𝘨𝘺𝘯𝘢), for fear of incurring the wrath of the aos sí, who use this plant as a portal between their world and ours. To this day, lone trees in particular are left well alone. In some cases, hawthorns are revered as rag trees with powers of healing, especially if growing by water or on a ringfort. This deep-rooted reluctance to interfere with certain wild things has the benefit of preserving nature. Hawthorn is superb for wildlife, providing shelter as well as food for animals, particularly when part of a hedgerow. Hedgerow habitats occupy an interface between open grassland and close-growing woodland. They have become increasingly important for biodiversity in the face of habitat loss and fragmentation, and intensifying land use. As well as a habitat in themselves, hedgerows also provide crucial links and landscape corridors for wildlife – many bats, for example, prefer not to cross open ground but use hedges and treelines to reach their insect-rich hunting grounds. Like Samhain, hedgerows occupy a liminal space, allowing some through while acting as a boundary for others.

One of the widespread medicinal plants known in Ireland is Sphagnum moss. A biological engineer, it is the very fabric of our raised bogs. Its power of absorption allow it to hold up to twenty two times its own weight in liquid. This remarkable sponge-like quality comes from its cellular structure – 90% of its cells are larger, hollow, and dead. It is also antiseptic, containing bacteria and fungi such as penicillin. Humans learned to take advantage of this capacity, using it to soak up blood, pus, and other bodily fluids. In Native American societies, it was used to line cradles, acting as a natural diaper. In Viking Age Dublin it was used as toilet paper. It is said that after the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, the armies used it to staunch their wounds. More recently, during World War One, it was again employed on the fronts. Both sides collected the moss and made extensive use of it. Nurses then began using it themselves during menstruation. Thus Sphagnum is an example of a plant whose properties were noted and utilised independently by different people.

A biological engineer, Sphagnum moss is the very fabric of our raised bogs. Its power of absorption allow it to hold up to twenty two times its own weight in liquid.

Nowadays we are not as intimately tied to the land so we are less in tune with the shifting seasons. Yet as we face the twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss, we find ourselves noticing nature and its cycles more than we did before. This coincides with renewed interest in our natural and built heritage as well as in customs and festivities such as Samhain.