The Shadow of the Witch

It’s all about the 23 degrees. The jolly tilt of our home planet, as it circles the sun yearly, has provided a rhythm in the lives of people, animals and plants—especially at temperate latitudes—since life on earth began. Over the millennia, and across continents, festivals and gatherings have developed around seasonal turning points. In China, Lidong is the equivalent of Halloween, as is Diwali in India and Martenmas in France. Setsubun in Japan is paralleled by Groundhog Day in the United States, and Saint Bridget’s Day in Ireland. Traditionally the four festivals of seasonal transition in Ireland were Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine and Lunasa. Just as the seasons inspired Greek drama, the ‘cross-quarter day’ festivals are the backdrop to the Gaelic texts. In legend and in folklore they mark the time of great battles or transitions, and moments of inauguration of kings. Samhain, the transition between summer’s end and the start of winter at the end of October, is a time of transformation and a festival of the dead. The discovery in 2008 that the central monument in Carrowmore—Listoghil—is aligned on sunrise at two of the critical season crossing dates left us with some interesting questions. For instance; could this design be interpreted as a physical representation of seasonal transits being celebrated in ancient Ireland?

Carrowmore, in County Sligo, is one of the most extensive clusters of Stone Age monuments in Ireland, with approximately 30 sites forming a nucleus at the core of the Cúil Iorra peninsula, all surrounding the central monument, Tomb 51 or Listoghil. On the fringes of this landmass low hills are punctuated on their summits by monuments of the same tradition, the IPTT, or Irish passage tomb tradition. A majority of the small satellite monuments and of the outlying sites are directed into the area at the centre of the peninsula, the location of the central monument.

Today we are in a moment of new discoveries. New work on the bones of the ancient dead—through the scientific techniques of osteology, stable isotopes of various elements and ancient DNA—has yielded a remarkable treasure trove of information about the lives and ancestral origins of the occupants of the Sligo monuments. Further research using lake coring tells us about their farming practices and about the vagaries of climate during a millennium of remarkable change in Ireland, starting with the arrival of the first farmers (about six thousand years ago) and culminating in a second invasion, that of the Beaker Folk at the outset of the Bronze Age. This is the story told by the guides and by the exhibition in the Office of Public Works Visitor Centre at Carrowmore (near Ransboro, about 4 km west of Sligo town). It is an account enriched by myth and legend as well as archaeology. The Neolithic era left a remarkable imprint on the landscape of Sligo; including many striking hill cairns, such as Knocknarea (with Queen Maeve’s Tomb), Keash Hill (with The Pinnacle on top) and the Ballygawley Mountains. Remarkably, many of these—up to a dozen—have never been excavated. Although folklore and quasi-historical accounts abound, no one really knows what they contain, or where they point to.

Listoghil, at the heart of Carrowmore, is a very different story. Tomb 51, as it is known by archaeologists, was greatly destroyed, probably towards the end of the 17th century. The authority of the Gaelic ascendancy had finally been broken by the arrival of parliamentarian and later royalist armies; this was a time of road building, bridge building and the lining of properties with field walls by landlords and merchants. The great English naturalist, Charles Elcock, accounted in the Proceedings of the Belfast Naturalists’ Field Club local descriptions of the use of the monument as a quarry, and the resulting discovery of the central chamber. This may have led to Listoghil becoming known locally as ‘The Cave’. A table-like dolmen with a mighty rooflslab lay swathed in a grass-covered uneven mound of irregular form with occasional boulders protruding.

All this changed in 1996 when the Swedish archaeologist Burenhult began the excavation of Carrowmore 51. His work revealed a very different monument to the smaller satellite tombs that surrounded it; they were mostly open in their architectural character and had been reused for burial repeatedly over the better part of a millennium. From the available data, it appears that Listoghil witnessed burial rituals over a comparatively shorter time period, perhaps a couple of centuries; then it was closed and covered by a stone mound.

The dead in Listoghil were treated differently, too. In the open boulder-built Carrowmore satellite monuments, cremation was the dominant funerary practice. Although cremations were discovered around some of the Listoghil kerbstones, at least seven people were placed unburnt in the inner chamber. Antiquarian digs disturbed this context, but gold standard (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry) carbon 14 dates, including one from bone, gave an indication of a narrow window of usage for the central monument at Carrowmore. Between 5400 and 5600 years ago human bones were deposited. Sometime later, the cairn was built up around the chamber. The builders appear to have constructed a passage—the exact form of which can never be known—to provide (and control) access.

There was one slightly macabre twist: one of the occupants of Listoghil, a male in his fifties, had been de-fleshed, possibly one of a suite of funerary treatments marking new innovations in the Irish Passage Tomb tradition (The burial ritual in Listoghil is echoed in Carrowkeel, the other great Sligo passage tomb cluster; Carrowkeel starts to be used for burial around the time of the building of Listoghil. There, bodies were dismembered using sharp stone tools). Another individual, a male in his twenties, was shown by DNA analysis in 2019 to be the father of a man buried in Primrose Grange, a monument located just two kilometres away on the slopes of Knocknarea.

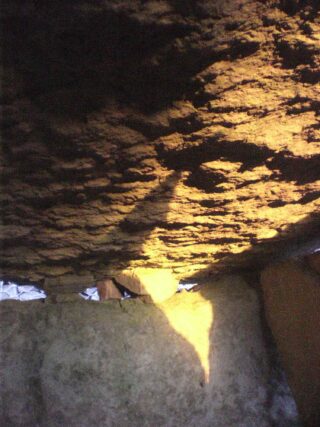

The connections of Carrowmore to the outlying hills were manifested in another way in 2008 when the sunrise at Halloween was first observed in modern times. The central chamber—although the outer cairn is a modern reconstruction, the chamber is still preserved in its original position—has a gable-shaped blocking stone to the front. It bears no weight and the point of the gable is rounded and polished by many hands. When the sun rises in alignment with the chamber, the shadow of this stone falls on the underside of the capstone. While every detail of this uneven surface stands out in the angled orange sunlight, the elongated shadow reaches over a meter long, like a spike of darkness centred on the belly of the roofslab. Gradually, as the sun rises, the shadow moves to the east and shortens. The effect lasts ten minutes.

Many visitors ask why so much Neolithic architecture in this landscape points towards the centre and towards Listoghil. The survey work in 2007 and subsequent observation sought to address this question. It was as if the monument—despite all its travails—still had something to tell us.

When the sun rises in alignment with the central chamber of Carrowmore it appears cupped in a natural saddle in the Ballygawley Mountains, six km away. Then, over the course of winter, after departing this natural hollow, the position of sunrise edges south as the days shorten. It crosses four rounded hills, each with a cairn on its summit; Aughamore Far, Sliabh Da Én, Sliabh Dargan, and Teach Cailleach a Bhérra, the house of the winter hag, Bhérra. The profile of the hills in folklore is visualised as the hag herself in repose with her head to the right (A similar figure in Callinish, Lewis in the Outer Hebrides is called the Cailleach na Móinteach). The arrival of sunrise to the top of the ‘head’ of the Cailleach marks standstill. The sun rises in virtually the same position for nearly two weeks as the season turns and the solstice is with us. The following weeks sees the position of sunrise travelling back across the reclining witch; and on February 10 the saddle again becomes the setting for the alignment event with Listoghil.

The idea of cyclicality is built into the Gaelic texts (like Queen Maeve’s cattle raid of Cooley, or the battle of Moytirra, a battle of light and dark forces, fought at a passage tomb cluster at Halloween). Temporal cyclicality is echoed in the symbolism of the antler pins accompanying the dead inside the Sligo passage tombs. The antlers are at their finest at Halloween, which is rutting season; stags deploy them as weapons in fights over females, and are lost in early spring. The mythic life of the Cailleach, who can be seen as a metaphor for a female earth, is cyclical too; she is frightening and dark in the winter and becomes young and fruitful in the spring. Perhaps here we catch a glimpse of the cosmology of the ancients; as John Waddell says there are echoes of these narratives in the Gundestrup cauldron and even in the cosmology of Ancient Egypt.

Local folklorists added to the background story, in particular the sculptor Michael Quirke. Other details were filled in by William Butler Yeats, who seems to have preserved elements of lore almost lost over the course of the twentieth century.

Such a mortal too was Clooth-na-bare, who went all over the world seeking a lake deep enough to drown her faery life, of which she had grown weary, leaping from hill to lake and lake to hill, and setting up a cairn of stones wherever her feet lighted, until at last she found the deepest water in the world in little Lough Ia, on the top of the Birds’ Mountain at Sligo

William Butler Yeats,

The Celtic Twilight, 1893

The Ballygawley Mountains are the locations of Sliabh Da Én (the Mountain of Two Birds) and Lough Da Gé (the lake of two geese, a hillside corrie lake, reputed to be bottomless). Yeats’ accounts (and those of other folklorists) shows how the cluster of four low hills was seen in totality as the Cailleach Bhérra, though in modern maps only one of the hills carries the name of the famous hag and sovereignty goddess. In a footnote Yeats’ observes that doubtless “Clooth-na-bare should be Cailleac Bare, which would mean the old Woman Bare”.

The width and depth of these traditions in the greater western European context is impressive. Authors like Cristobo Carrín and Gearoid Ó Crualaoich describe the Cailleach or Gawres, or La Vieja (the giantess or hag), as virtually ubiquitous as a symbol of nature and seasonality in Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Spain. She rules the winter, and is ‘defeated’ by the arrival of spring. She is connected in folklore to natural rock formations or ancient monuments. A version of her appears to have been Christianised as Saint Bridget. Traditional narratives and rituals are faintly detectable in modern day myths. We still celebrate witches, divination, and the change of seasons in our Halloween traditions. Even in cultures geographically remote from each other and connected only by the 23 degree tilt of the Earth, similar themes occur. In Japan at Setsubun in February revellers throw beans at a heavily dressed up demon, an equivalent to the winter witch.

The Listoghil phenomenon is shared with another very famous Irish site, Dumha na nGiall, the Mound of the Hostages at Tara. This site was in use around the time of Listoghil, but the chamber and cairn were constructed perhaps two hundred years later. In recent years we have had the opportunity to observe at both sites and compare notes. The chamber of the Mound of the Hostages is aligned to the distant Wicklow Hills and the island of Lambay. At approximately 7.25 am on the 31 October the sun rises and casts a quadrilateral of faint pink light on the vegetation-covered backstone of DNG. On that date, the sun rises in perfect alignment with the chamber. Meanwhile in Sligo the anticipation is building, and the Ballygawley Mountains are backlit with a deep orange glow. 17 minutes later the planet has rolled on its axis enough, and the solar climb from behind the Ballygawley Mountains is complete. A golden sliver of sun breaks the saddle and the spike of shadow suddenly appears on the capstone underside of Listoghil. Perhaps this congruence is coincidental; certainly it is a remarkable one.

These days the sunrise event at Carrowmore is celebrated by Office of Public Works staff in conjunction with the local community, the Ransboro Development Association. The RDA supply tea and buns, and join visitors and guides in hoping for a clear morning. Even if the sun does not oblige, the atmosphere is enthusiastic and celebratory. The centre opens at 7.15 am and sunrise occurs between 7.40 and 8.00 am. Usually a slide show/ talk is conducted in the centre afterwards to wrap up proceedings.

Pádraig Meehan is a writer and researcher; his field of interest is the Irish Passage Tomb Tradition. As a member of the Human Population Dynamics at Carrowkeel international archaeology research team, he has co-authored a recent series of papers. He has also published articles and a book on the topic of the Listoghil alignment. Pádraig works as a guide in Carrowmore visitor centre, Sligo.